Bạn nhận biết được tình yêu khi tất cả những gì bạn muốn là mang đến niềm vui cho người mình yêu, ngay cả khi bạn không hiện diện trong niềm vui ấy. (You know it's love when all you want is that person to be happy, even if you're not part of their happiness.)Julia Roberts

Khi gặp phải thảm họa trong đời sống, ta có thể phản ứng theo hai cách. Hoặc là thất vọng và rơi vào thói xấu tự hủy hoại mình, hoặc vận dụng thách thức đó để tìm ra sức mạnh nội tại của mình. Nhờ vào những lời Phật dạy, tôi đã có thể chọn theo cách thứ hai. (When we meet real tragedy in life, we can react in two ways - either by losing hope and falling into self-destructive habits, or by using the challenge to find our inner strength. Thanks to the teachings of Buddha, I have been able to take this second way.)Đức Đạt-lai Lạt-ma XIV

Tôi phản đối bạo lực vì ngay cả khi nó có vẻ như điều tốt đẹp thì đó cũng chỉ là tạm thời, nhưng tội ác nó tạo ra thì tồn tại mãi mãi. (I object to violence because when it appears to do good, the good is only temporary; the evil it does is permanent.)Mahatma Gandhi

Để có thể hành động tích cực, chúng ta cần phát triển một quan điểm tích cực. (In order to carry a positive action we must develop here a positive vision.)Đức Đạt-lai Lạt-ma XIV

Thành công là khi bạn đứng dậy nhiều hơn số lần vấp ngã. (Success is falling nine times and getting up ten.)Jon Bon Jovi

Chúng ta không thể giải quyết các vấn đề bất ổn của mình với cùng những suy nghĩ giống như khi ta đã tạo ra chúng. (We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.)Albert Einstein

Cuộc sống ở thế giới này trở thành nguy hiểm không phải vì những kẻ xấu ác, mà bởi những con người vô cảm không làm bất cứ điều gì trước cái ác. (The world is a dangerous place to live; not because of the people who are evil, but because of the people who don't do anything about it.)Albert Einstein

Ai dùng các hạnh lành, làm xóa mờ nghiệp ác, chói sáng rực đời này, như trăng thoát mây che.Kinh Pháp cú (Kệ số 173)

Việc người khác ca ngợi bạn quá hơn sự thật tự nó không gây hại, nhưng thường sẽ khiến cho bạn tự nghĩ về mình quá hơn sự thật, và đó là khi tai họa bắt đầu.Rộng Mở Tâm Hồn

Mỗi cơn giận luôn có một nguyên nhân, nhưng rất hiếm khi đó là nguyên nhân chính đáng. (Anger is never without a reason, but seldom with a good one.)Benjamin Franklin

Hãy lắng nghe trước khi nói. Hãy suy ngẫm trước khi viết. Hãy kiếm tiền trước khi tiêu pha. Hãy dành dụm trước khi nghỉ hưu. Hãy khảo sát trước khi đầu tư. Hãy chờ đợi trước khi phê phán. Hãy tha thứ trước khi cầu nguyện. Hãy cố gắng trước khi bỏ cuộc. Và hãy cho đi trước khi từ giã cuộc đời này. (Before you speak, listen. Before you write, think. Before you spend, earn. Before you retire, save. Before you invest, investigate. Before you critisize, wait. Before you pray, forgive. Before you quit, try. Before you die, give. )Sưu tầm

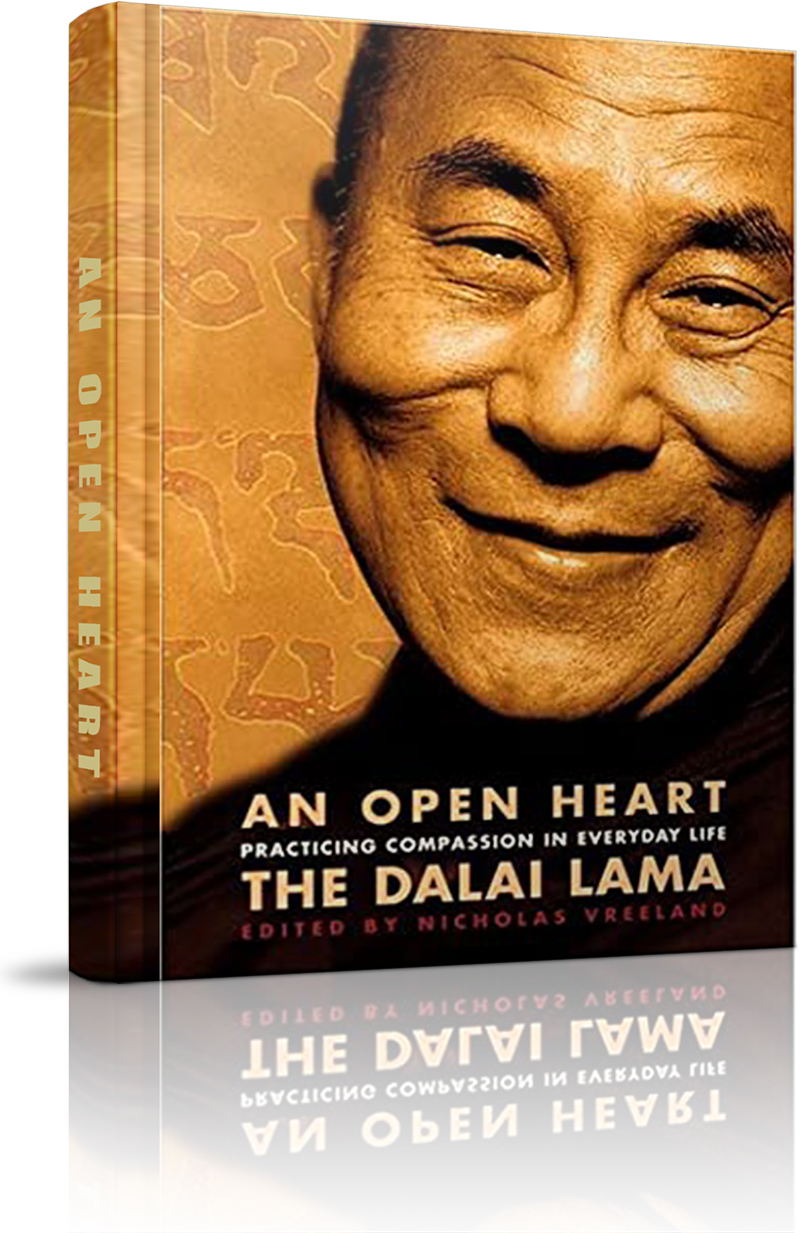

Trang chủ »» Danh mục »» SÁCH ANH NGỮ HOẶC SONG NGỮ ANH-VIỆT »» An Open Heart »» Chapter 3: The material and immaterial world »»

Xem Mục lục

Xem Mục lục  Vietnamese || Đối chiếu song ngữ

Vietnamese || Đối chiếu song ngữ

DO NXB LIÊN PHẬT HỘI PHÁT HÀNH

Mua sách qua Amazon sẽ được gửi đến tận nhà - trên toàn nước Mỹ, Canada, Âu châu và Úc châu.

Quý vị đang truy cập từ IP 216.73.216.175 và chưa ghi danh hoặc đăng nhập trên máy tính này. Nếu là thành viên, quý vị chỉ cần đăng nhập một lần duy nhất trên thiết bị truy cập, bằng email và mật khẩu đã chọn.

Chúng tôi khuyến khích việc ghi danh thành viên ,để thuận tiện trong việc chia sẻ thông tin, chia sẻ kinh nghiệm sống giữa các thành viên, đồng thời quý vị cũng sẽ nhận được sự hỗ trợ kỹ thuật từ Ban Quản Trị trong quá trình sử dụng website này.

Việc ghi danh là hoàn toàn miễn phí và tự nguyện.

Ghi danh hoặc đăng nhập