Phán đoán chính xác có được từ kinh nghiệm, nhưng kinh nghiệm thường có được từ phán đoán sai lầm. (Good judgment comes from experience, and often experience comes from bad judgment. )Rita Mae Brown

Người thực hành ít ham muốn thì lòng được thản nhiên, không phải lo sợ chi cả, cho dù gặp việc thế nào cũng tự thấy đầy đủ.Kinh Lời dạy cuối cùng

Hạnh phúc chân thật là sự yên vui, thanh thản mà mỗi chúng ta có thể đạt đến bất chấp những khó khăn hay nghịch cảnh. Tủ sách Rộng Mở Tâm Hồn

Khi tự tin vào chính mình, chúng ta có được bí quyết đầu tiên của sự thành công. (When we believe in ourselves we have the first secret of success. )Norman Vincent Peale

Nếu muốn đi nhanh, hãy đi một mình. Nếu muốn đi xa, hãy đi cùng người khác. (If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together.)Ngạn ngữ Châu Phi

Trong cuộc sống, điều quan trọng không phải bạn đang ở hoàn cảnh nào mà là bạn đang hướng đến mục đích gì. (The great thing in this world is not so much where you stand as in what direction you are moving. )Oliver Wendell Holmes

Dễ thay thấy lỗi người, lỗi mình thấy mới khó.Kinh Pháp cú (Kệ số 252)

Hãy đạt đến thành công bằng vào việc phụng sự người khác, không phải dựa vào phí tổn mà người khác phải trả. (Earn your success based on service to others, not at the expense of others.)H. Jackson Brown, Jr.

Yêu thương và từ bi là thiết yếu chứ không phải những điều xa xỉ. Không có những phẩm tính này thì nhân loại không thể nào tồn tại. (Love and compassion are necessities, not luxuries. Without them humanity cannot survive.)Đức Đạt-lai Lạt-ma XIV

Niềm vui cao cả nhất là niềm vui của sự học hỏi. (The noblest pleasure is the joy of understanding.)Leonardo da Vinci

Nay vui, đời sau vui, làm phước, hai đời vui.Kinh Pháp Cú (Kệ số 16)

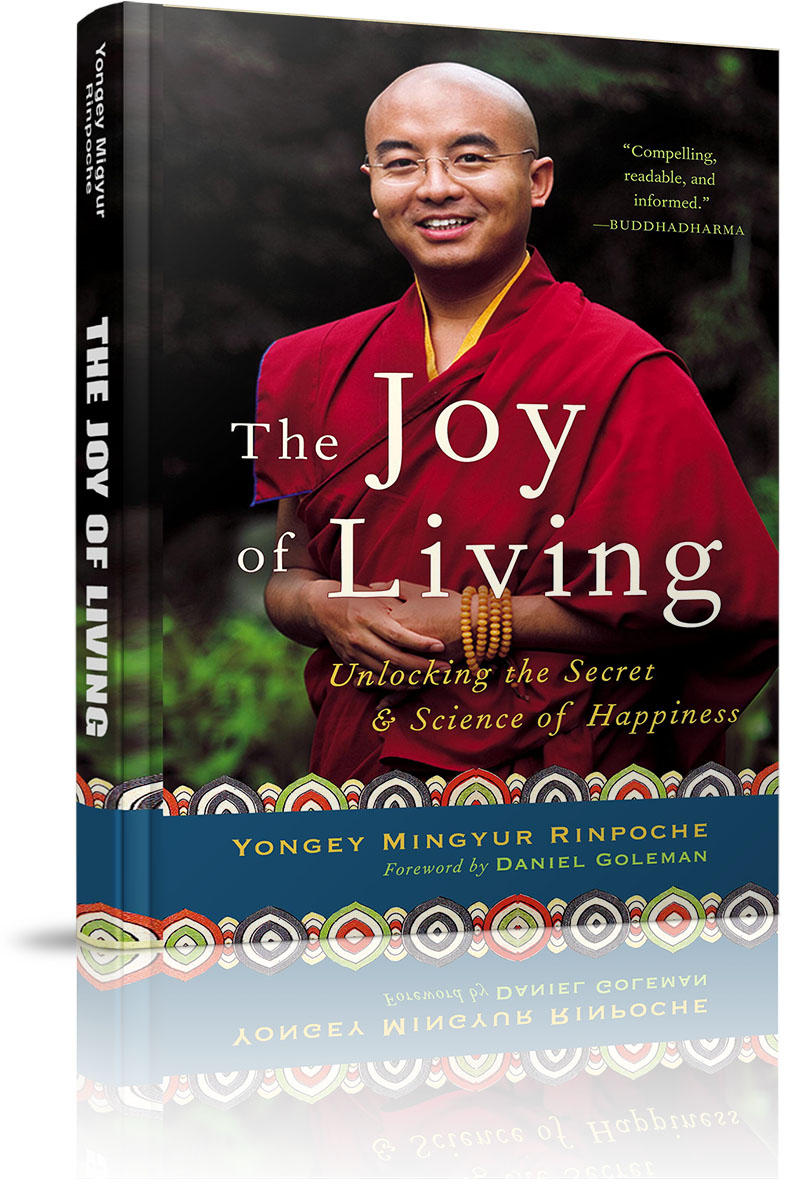

Trang chủ »» Danh mục »» SÁCH ANH NGỮ HOẶC SONG NGỮ ANH-VIỆT »» The Joy of Living »» 8. Why are we unhappy? »»

The Joy of Living

»» 8. Why are we unhappy?

Xem Mục lục

Xem Mục lục  Vietnamese || Đối chiếu song ngữ

Vietnamese || Đối chiếu song ngữ

- none

- Introduction

- Part One: The Ground - 1. The Journey Begins

- 2. The inner symphony

- 3. Beyond the mind, beyond the brain

- Emptiness: The reality beyond reality

- The relativity of perception

- 6. The Gift of Clarity

- 7. Compassion: Survival of the kindest

- »» 8. Why are we unhappy?

- Part Two: The Path - 9. Finding Your Balance

- 10. Simply resting: The first step

- 11. Next steps: Resting on objects

- 12. Working with thoughts and feelings

- 13. Compassion: Opening the heart of the mind

- 14. The how, when, and where of practice

- Part Three: The fruit - 15. Problems and Possibility

- 16. An inside job

- 17. The biology of happiness

- 18. Moving on

- none

- JAMGON KONGTRUL, The Torch of Certainty, translated by Judith Hanson

After almost ten years of teaching in more than twenty countries around the world, I’ve seen a lot of strange and wonderful things, and heard a lot of strange and wonderful stories from people who have spoken up at public teachings or come to me for private counseling. What’s surprised me most, though, was to see that people living in places where material comforts were widely available appeared to experience a depth of suffering similar to what I’d seen among those who lived in places that weren’t quite so materially developed. The expression of suffering I witnessed was different in some respects from what I’d become accustomed to witnessing in India and Nepal, but its strength was palpable.

I began to sense this level of unhappiness during my first few visits to the West, when my hosts would take me to see the great landmarks in their cities. When I first saw places like the Empire State Building or the Eiffel Tower, I couldn’t help but be struck by the genius of the designers and the degree of cooperation and determination that must have been required of the people who built these structures. But when we arrived at the observation deck, I’d find the view blocked by barbed-wire fencing and the whole area patrolled by guards. When I asked my hosts about the guards and fences, they explained that the precautions were necessary to keep people from killing themselves by jumping from the heights. It seemed immeasurably sad to me that societies capable of producing such wonders would need to impose strict measures to keep people from using these beautiful monuments as platforms for suicide.

The security measures didn’t detract at all from my appreciation of the beauty of these places or the technological skill required to build them. But after I’d visited a few of these places, the security precautions began to “click into place” with something else I’d begun to notice. Although people living in materially comfortable cultures tended to smile easily enough, their eyes almost always betrayed a sense of dissatisfaction and even desperation. And the questions people asked during both public and private talks often seemed to revolve around how to become better or stronger than they were, or how to get over “self-hatred.”

The more widely I traveled, the clearer it became to me that people living in societies characterized by technological and material achievements were just as likely to feel pain, anxiety, loneliness, isolation, and despair as people who lived in comparatively less-developed areas. After a few years of asking some very pointed questions in public teachings and in private counseling sessions, I began to see that when the pace of external or material progress exceeded the development of inner knowledge, people seemed to suffer deep emotional conflicts without any internal method of dealing with them. An abundance of material items provides such a variety of external distractions that people lose the connection to their inner lives.

Just think, for example, about the number of people who desperately look for a sense of excitement by going to a new restaurant, starting a new relationship, or moving to a different job. For a while the newness does seem to provide some sense of stimulation. But eventually the excitement dies down; the new sensations, new friends, or new responsibilities become commonplace. Whatever happiness they originally felt dissolves.

So they try a new strategy, like going to the beach. And for a while that seems satisfying, too. The sun feels warm, the water feels great, and there’s a whole new crowd of people to meet, and maybe new and exciting activities to try, like jet skiing or parasailing. But after a while, even the beach gets boring. The same old conversations are repeated over and over, the sand feels gritty on your skin, the sun is too strong or hides behind clouds, and the ocean gets cold. So it’s time to move on, try a different beach, maybe in a different country. The mind produces its own sort of mantra: “I want to go to Tahiti . . . Tahiti . . . Tahiti. . . .”

The trouble with all of these solutions is that they are, by nature, temporary. All phenomena are the results of the coming together of causes and conditions, and therefore inevitably undergo some type of change. When the underlying causes that produced and perpetuated an experience of happiness change, most people end up blaming either external conditions (other people, a place, the weather, etc.) or themselves (“I should have said something nicer or smarter,” “I should have gone somewhere else”). However, because it reflects a loss of confidence in oneself, or in the things we’re taught to believe should bring us happiness, blame only makes the search for happiness more difficult.

The more problematic issue is that most people don’t have a very clear idea of what happiness is, and consequently find themselves creating conditions that lead them back to the dissatisfaction they so desperately seek to eliminate. That being the case, it would be a good idea to look at happiness, unhappiness, and their underlying causes a bit more closely.

THE EMOTIONAL BODY

There is no one center for emotion, just as there is none for playing tennis.

- RICHARD DAVIDSON, quoted in Daniel Goleman, Destructive Emotions: How Can We Overcome Them?

Our bodies play a much bigger role in the generation of emotions than most of us recognize. The process begins with perception - which we already know involves the passing of information from sensory organs to the brain, where a conceptual representation of an object is created. Most of us would assume, quite naturally, that once the object is perceived and recognized, an emotional response is produced, which in turn generates some sort of physical reaction.

In fact, the opposite occurs. At the same time that the thalamus sends its messages higher up to the analytical regions of the brain, it sends a simultaneous “red alert” message to the amygdala, the funny little walnut-shaped neuronal structure in the limbic region, which, as described earlier, governs emotional responses, particularly fear and anger. Because the thalamus and the amygdala are very close to each other, this red alert signal travels much more quickly than the messages sent to the neocortex. Upon receiving it, the amygdala immediately sets in motion a series of physical responses that activate the heart; the lungs; major muscles groups in the arms, chest, abdomen, and legs; and the organs responsible for producing hormones like adrenaline. Only after the body responds does the analytical part of the brain interpret the physical reactions in terms of a specific emotion.

In other words, you don’t see something scary, feel fear, and then run. You see something scary, start to run (as your heart pounds and adrenaline surges through your body), and then interpret the body’s reaction as fear. In most cases, though, once the rest of your brain has caught up with your body, which takes only a few milliseconds, you’re able to assess your reactions and determine whether they’re appropriate, as well as adjust your behavior to fit the particular situation.

The results of this assessment can actually be measured by technology that has only recently become available to scientists. Emotions such as fear, disgust, and loathing appear in part as a heightened activation of neurons in the right frontal lobe, the region of the neocortex located at the very front of the right side of the brain. Meanwhile, emotions such as joy, love, compassion, and confidence can be measured in terms of relatively greater activity among the neurons in the left frontal lobe.

In some instances, I’ve been told, our ability to evaluate our reactions is inhibited, and we find ourselves responding to a situation without thinking. In such cases the amygdala’s response is so strong that it short-circuits the reaction of the higher brain structures. Such a powerful “emergency response” mechanism undoubtedly has important survival benefits, enabling us to immediately recognize foods that once made us sick, or to avoid aggressive animals. But because the neuronal patterns stored in the amygdala can be triggered easily by events that bear even a slight resemblance to an earlier incident, they can distort our perception of present-moment events.

STATES AND TRAITS

Everything depends on circumstance.

- PATRUL RINPOCHE, The Words of My Perfect Teacher, translated by the Padmakara Translation Group

From a scientific perspective, emotions are viewed in terms of short-term events and longer-lasting conditions. Short-term emotions might include the sudden burst of anger we experience when we’re fixing something around the house and accidentally hit our thumb with a hammer, or the swell of pride we feel when someone pays us a genuine compliment. In scientific terms, these relatively short-term events are often referred to as states.

Emotions that continue over time and across a variety of situations, such as the love someone feels for a child or a lingering resentment over something that happened in the past, are referred to as traits or temperamental qualities, which most of us regard as indicators of a person’s character. For example, we tend to say that a person who is usually smiling and energetic and always has nice things to say to other people is a “cheerful” person, while we tend to think of someone who frowns a lot, runs around in a hurry, hunches over his desk, and loses his temper over little things as a “tense” person.

The difference between states and traits is fairly obvious, even to someone who doesn’t have a science degree. If you hit your thumb with a hammer, chances are good that the anger you experience will pass fairly quickly and won’t cause you to be afraid of hammers for the rest of your life. Emotional traits are more subtle. In most cases we’re able to recognize whether we wake up anxious or excited day after day, while indications of our temperament gradually become evident over time to others with whom we’re in close contact.

Emotional states are fairly quick bursts of neuronal gossip. Traits, on the other hand, are more like the neuronal equivalent of committed relationships. The origins of these long-lasting connections may vary. Some may have a genetic basis, others may be caused by serious trauma, and still others may simply have developed as a result of sustained or repeated experiences - the life training we receive as children and young adults.

Whatever their origin, emotional traits have a conditioning effect on the way people characterize and respond to their everyday experiences. Someone predisposed to fear or depression, for example, is more likely to approach situations with a sense of trepidation, whereas someone disposed toward confidence will approach the same situation with much more poise and assurance.

CONDITIONING FACTORS

Suffering follows a negative thought as the wheels of a cart follow

the oxen that draw it.

- The Dhammapada, translated by Eknath Easvvaran

Biology and neuroscience tell us what’s going on in our brains when we experience pleasant or unpleasant emotions. Buddhism helps us not only to describe such experiences more explicitly to ourselves, but also provides us with the means to go about changing our thoughts, feelings, and perceptions so that on a basic, cellular level we can become happier, more peaceful, and more loving human beings.

Whether looked at subjectively through mindful observation taught by the Buddha, or objectively, through the technology available in modern laboratories, what we call the mind emerges as a constantly shifting collision of two basic events: bare recognition (the simple awareness that something is happening) and conditioning factors (the processes that not only describe what we perceive, but also determine our responses). All mental activity, in other words, evolves from the combined activity of bare perception and long-term neuronal associations.

One of the lessons repeated again and again by my teacher Saljay Rinpoche was that if I wanted to be happy, I had to learn to recognize and work with the conditioning factors that produce compulsive or trait-bound reactions. The essence of his teaching was that any factor can be understood as compulsive to the degree that it obscures our ability to see things as they are, without judgment. If someone is yelling at us, for example, we rarely take the time to distinguish between the bare recognition “Oh, this person is raising his voice and saying such and such words” and the emotional response “This person is a jerk.” Instead, we tend to combine bare perception and our emotional response into a single package: “This person is screaming at me because he’s a jerk.”

But if we could step back to look at the situation more objectively, we might see that people who yell at us are upset over something that may have nothing to do with us. Maybe they just got criticized by someone higher up and are afraid of getting fired. Maybe they just found out that someone close to them is very sick. Or maybe they had an argument with a friend or a partner and didn’t sleep well afterward. Sadly, the influence of conditioning is so strong that we rarely remember that we can step back. And because our understanding is limited, we mistake the little part we do see for the whole truth.

How can we respond appropriately when our vision is so limited, when we don’t have all the facts? If we apply the standard of American courts to tell “the whole truth and nothing but the truth” about our everyday experience, we must recognize that the “whole truth” is that everyone just wants to be happy. The truly sad thing is that most people seek happiness in ways that actually sabotage their attempts. If we could see the whole truth of any situation, our only response would be one of compassion.

MENTAL AFFLICTIONS

By whom and how were the weapons of hell created?

- SANTIDEVA, The Bodhicaryavatara, translated by Kate Crosby and Andrew Skilton

The conditioning factors are often referred to in Buddhist terms as “mental afflictions,” or sometimes “poisons.” Although the texts of Buddhist psychology examine a wide range of conditioning factors, all of them agree in identifying three primary afflictions that form the basis of all other factors that inhibit our ability to see things as they really are: ignorance, attachment, and aversion.

Ignorance

Ignorance is a fundamental inability to recognize the infinite potential, clarity, and power of our own minds, as if we were looking at the world through colored glass: Whatever we see is disguised or distorted by the colors of the glass. On the most essential level, ignorance distorts the basically open experience of awareness into dualistic distinctions between inherently existing categories of “self and “other.”

Ignorance is thus a twofold problem. Once we establish the neuronal habit of identifying ourselves as a single, independently existing “self,” we inevitably start to see whatever is not “self as “other.” “Other” can be anything: a table, a banana, another person, or even something this “self is thinking or feeling. Everything we experience becomes, in a sense, a stranger. And as we become accustomed to distinguishing between “self” and “other,” we lock ourselves into a dualistic mode of perception, drawing conceptual boundaries between our “self” and the rest of the world “out there,” a world that seems so vast that we almost can’t help but begin to think of ourselves as very small, limited, and vulnerable. We begin looking at other people, material objects, and so on as potential sources of happiness and unhappiness, and life becomes a struggle to get what we need in order to be happy before somebody else grabs it.

This struggle is known in Sanskrit as samsara, which literally means “wheel” or “circle.” Specifically, samsara refers to the wheel or circle of unhappiness, a habit of running around in circles, chasing after the same experiences again and again, each time expecting a different result. If you’ve ever watched a dog or a cat chasing its own tail, you’ve seen the essence of samsara. And even though it might be funny to watch an animal chase its tail, it’s not so funny when your own mind does the same thing.

The opposite of samsara is nirvana, a term that is almost as completely misunderstood as emptiness. A Sanskrit word roughly translated as “extinguishing” or “blowing out” (as in the blowing out of the flame of a candle), nirvana is often interpreted as a state of total bliss or happiness, arising from the extinguishing or “blowing out” of the ego or the idea of “self.” This interpretation is accurate to a certain extent, except that it doesn’t take into account that most of us live as embodied beings going about our lives in the relatively real world of moral, ethical, legal, and physical distinctions.

Trying to live in this world without abiding by its relative distinctions would be as foolish and difficult as trying to avoid the consequences of being born right- or left-handed. What would be the point? A more precise interpretation of nirvana is the adoption of a broad perspective that admits all experiences, pleasurable or painful, as aspects of awareness. Naturally, most people would prefer to experience only the “high notes” of happiness. But as a student of mine recently pointed out, eliminating the “low notes” from a Beethoven symphony - or any modern song, for that matter - would result in a pretty cheap and tinny experience.

Samsara and nirvana are perhaps best understood as points of view. Samsara is a point of view based primarily on defining and identifying with experiences as either painful or unpleasant. Nirvana is a fundamentally objective state of mind: an acceptance of experience without judgments, which opens us to the potential for seeing solutions that may not be directly connected to our survival as individuals, but rather to the survival of all sentient beings.

Which brings us to the second of the three primary mental afflictions.

Attachment

The perception of “self as separate from “others” is, as discussed earlier, an essentially biological mechanism - an established pattern of neuronal gossip that consistently signals other parts of the nervous system that each of us is a distinct, independently existing creature that needs certain things in order to perpetuate its existence. Because we live in physical bodies, some of these things we need, such as oxygen, food, and water, are truly indispensable. In addition, studies of infant survival that people have discussed with me have shown that survival requires a certain amount of physical nurturing. We need to be touched; we need to be spoken to; we need the simple fact of our existence to be acknowledged.

Problems begin, however, when we generalize biologically essential things into areas that have nothing to do with basic survival. In Buddhist terms, this generalization is known as “attachment” or “desire” - which, like ignorance, can be seen as having a purely neurological basis.

When we experience something like chocolate, for example, as pleasant, we establish a neuronal connection that equates chocolate with the physical sensation of enjoyment. This is not to say that chocolate in itself is a good or bad thing. There are lots of chemicals in chocolate that create a physical sensation of pleasure. It’s our neuronal attachment to chocolate that creates problems.

Attachment is in many ways comparable to addiction, a compulsive dependency on external objects or experiences to manufacture an illusion of wholeness. Unfortunately, like other addictions, attachment becomes more intense over time. Whatever satisfaction we might experience when we attain something or someone we desire doesn’t last. Whatever or whoever made us happy today, this month, or this year is bound to change. Change is the only constant of relative reality.

The Buddha compared attachment to drinking salt water from an ocean. The more we drink, the thirstier we get. Likewise, when our mind is conditioned by attachment, however much we have, we never really experience contentment. We lose the ability to distinguish between the bare experience of happiness and whatever objects temporarily make us happy. As a result, we not only become dependent on the object, but we also reinforce the neuronal patterns that condition us to rely on an external source to give us happiness.

You can substitute any number of objects for chocolate. For some people, relationships are the key to happiness. When they see someone they think is attractive, they try all kinds of ways to approach him or her. But if they finally manage to become involved with that person, the relationship doesn’t turn out to be as satisfying as they imagined. Why? Because the object of their attachment is not really an external thing. It’s a story spun by the neurons in the brain; and that story unfolds on many different levels, ranging from what they think they might gain from achieving what they desire to what they fear if they fail to get it.

Other people think they’d be really happy if they experienced an extreme stroke of good luck, like winning the lottery. But an interesting study by Philip Brinkman that I heard about from one of my students has shown that people who had recently won a lottery were not that much happier than a control group who hadn’t experienced the excitement of suddenly becoming rich. In fact, after the initial thrill wore off, the people who’d won a lottery reported finding less enjoyment in the everyday pleasures, like chatting with friends, getting compliments, or simply reading a magazine, than people who hadn’t experienced such a major change.

The study reminded me of a story I heard not long ago about an old man who’d bought a ticket for a lottery worth more than a hundred million dollars. A short time after buying the ticket, he developed a heart problem and was sent to the hospital under the care of a doctor who ordered strict bed rest and absolutely forbade anything that would cause undue excitement. While the old man was in the hospital, his ticket actually won the lottery. Since he was in a hospital, of course, the old man didn’t know about his good fortune, but his children and his wife found out and went to the hospital to tell the man the news.

On the way to his hospital room, they met his doctor and told him all about the old man’s good fortune. As soon as they’d finished, the doctor pleaded with them not to say anything just yet. “He might get so excited,” the doctor explained, “that he could die from the strain on his heart.” The man’s wife and children argued with the doctor, believing that the good news would help improve his condition. But in the end they agreed to let the doctor break the news, gently and slowly so as not to cause the man undue excitement.

While the man’s wife and children sat waiting in the hall, the doctor went into his patient’s room. He began by asking the man all sorts of questions about his symptoms, how he was feeling, and so on; and after a while, he asked, very casually, “Have you ever bought a ticket for the lottery?”

The old man replied that, in fact, he had bought a ticket just before coming to the hospital.

“If you won the lottery,” the doctor asked, “how would you feel?”

“Well, if I do, that would be nice. If I don’t, that would be fine, too. I’m an old man and won’t live much longer. Whether I win or not, it doesn’t really matter.”

“You couldn’t really feel that way,” the doctor said, in the manner of someone speaking purely theoretically. “If you won, you’d be really excited, right?”

But the old man replied, “Not really. In fact, I’d be happy to give you half of it if you could find a way to make me feel better.”

The doctor laughed. “Don’t even think about it,” he said. “I was just asking.”

But the patient insisted, “No, I mean it. If I won the lottery, I really would give you half of what I won if you could make me feel better.”

Again, the doctor laughed. “Why don’t you write a letter,” he joked, “saying you’d give me half?”

“Sure, why not?” the old man agreed, reaching over to the table next to his bed and picking up a pad of paper. Slowly, feebly, he wrote out a letter agreeing to give the doctor half of any lottery money he might win, signed it, and handed it to the doctor. When the doctor looked at the letter and the signature, he got so excited over the idea of getting so much money that he fell over dead on the spot.

As soon as the doctor fell, the old man started shouting. Hearing the noise, the man’s wife and children feared that the doctor had been right all along, that the news really had been too exciting, and the old man crumplehad died from the strain on his heart. They rushed into the room, only to find the old man sitting up in his bed and the doctor crumpled on the floor. While the nurses and other hospital staff rushed around trying to revive the doctor, the old man’s family quietly told him that he had won the lottery. Much to their surprise, he didn’t seem all that excited about learning that he’d just won millions of dollars, and the news didn’t do him any damage at all. In fact, after a few weeks his condition improved and he was released from the hospital. Certainly he was glad to enjoy his new wealth, but he wasn’t all that attached to it. The doctor, on the other hand, had been so attached to the idea of having so much money, and his excitement was so great, that his heart couldn’t bear the strain and he died.

Aversion

Every strong attachment generates an equally powerful fear that we’ll either fail to get what we want or lose whatever we’ve already gained. This fear, in the language of Buddhism, is known as aversion: a resistance to the inevitable changes that occur as a consequence of the impermanent nature of relative reality.

The notion of a lasting, independently existing self urges us to expend enormous effort in resisting the inevitability of change, making sure that this “self” remains safe and secure. When we’ve achieved some condition that makes us feel whole and complete, we want everything to stay exactly as it is. The deeper our attachment to whatever provides us with this sense of completeness, the greater our fear of losing it, and the more brutal our pain if we do lose it.

In many ways, aversion is a self-fulfilling prophecy, compelling us to act in ways that practically guarantee that our efforts to attain whatever we think will bring us lasting peace, stability, and contentment will fail. Just think for a moment about how you act around someone to whom you feel a strong attraction. Do you behave like the suave, sophisticated, and self-confident person you’d like the other person to see, or do you suddenly become a tongue-tied goon? If this person talks and laughs with someone else, do you feel hurt or jealous, and betray your pain and jealousy in small or obvious ways? Do you become so fiercely attached to the other person to such a degree that he or she senses your desperation and begins to avoid you?

Aversion reinforces neuronal patterns that generate a mental construct of yourself as limited, weak, and incomplete. Because anything that might undermine the independence of this mentally constructed “self” is perceived as a threat, you unconsciously expend an enormous amount of energy on the lookout for potential dangers. Adrenaline rips through your body, your heart races, your muscles tense, and your lungs pump like mad. All these sensations are symptoms of stress, which, as I’ve heard from many scientists, can cause a huge variety of problems, including depression, sleeping disorders, digestive problems, rashes, thyroid and kidney malfunctions, high blood pressure, and even high cholesterol.

On a purely emotional level, aversion tends to manifest as anger and even hatred. Instead of recognizing that whatever unhappiness you feel is based on a mentally constructed image, you find it only “natural” to blame other people, external objects, or situations for your pain. When people behave in a way that appears to prevent you from obtaining what you desire, you begin to think of them as untrustworthy or mean, and you’ll go out of your way either to avoid them or strike back at them. In the grip of anger, you see everyone and everything as enemies. As a result, your inner and outer worlds become smaller and smaller. You lose faith in yourself, and reinforce specific neuronal patterns that generate feelings of fear and vulnerability.

AFFLICTION OR OPPORTUNITY?

Consider the advantages of this rare human existence.

- JAMGON KONGTRUL, The Torch of Certainty, translated by Judith Hanson

It’s easy to think of mental afflictions as defects of character. But that would be a devaluation of ourselves. Our capacity for emotions, for distinguishing between pain and pleasure, and tor experiencing “gut responses” has played and continues to play a critical survival function, enabling us almost instantaneously to adapt to subtle changes in the world around us, and to formulate those adaptations consciously so that we can recall them at will and pass them along to succeeding generations.

Such extraordinary sensitivity reinforces one of the most basic lessons taught by the Buddha, which was to consider how precious this human life is, with all its freedoms and opportunities; how difficult it is to obtain such a life; and how easy it is to lose it.

It doesn’t matter whether you believe that human life is a cosmic accident, a karmic lesson, or the work of a divine creator. If you simply pause to consider the huge variety and number of creatures that share the planet with us, compared with the relatively small percentage of human beings, you have to conclude that the chances of being born as a human being are extremely rare. And in demonstrating the extraordinary complexity and sensitivity of the human brain, modern science reminds us how fortunate we are to have been born human, with the very human capacity to feel and to sense the feelings of those around us.

From a Buddhist standpoint, the automatic nature of human emotional tendencies represents an interesting challenge. It doesn’t require a microscope to observe psychological habits; most people don’t have to look any further than their last relationship. They begin by thinking, This time it’s going to be different. A few weeks, months, or years later, they smack their heads, thinking, Oh no, this is exactly the same type of relationship I was involved in before.

Or you can look at your professional life. You start a new job thinking, This time I’m not going to end up spending hours and hours working late, only to get criticized for not doing enough. Yet three or four months into the job, you find yourself canceling appointments or calling friends to say, “I can’t make dinner tonight. I have too much work to do.”

Despite your best intentions, you find yourself repeating the same patterns while expecting a different result.

Many of the people I’ve worked with over the years have talked about how they daydreamed about getting through the week so they could enjoy the weekend. But when the weekend is over, they’re back at their desks for another week, daydreaming about the next weekend. Or they tell me about how they’ve invested enormous time and effort in completing a project, but never allow themselves to experience any sense of accomplishment because they have to start working on the next task on their list. Even when they’re relaxing, they say they’re preoccupied by something that happened the previous week, the previous month, or even the previous year, replaying scenes over and over in their minds, trying to figure out what they could have done to make the outcome more satisfying.

Fortunately, the more familiar we become with examining our minds, the closer we come to finding a solution to whatever problem we might be facing, and the more easily we recognize that whatever we experience - attachment, aversion, stress, anxiety, fear, or longing - is simply a fabrication of our own minds.

People who have invested a sincere effort in exploring their inner wealth naturally tend to develop a certain kind of fame, respect, and credibility, regardless of their external circumstances. Their conduct in all kinds of situations inspires in others a profound sense of respect, admiration, and trust. Their success in the world has nothing to do with personal ambition or a craving for attention. It doesn’t come from owning a nice car or a beautiful home, or having an important job title. It stems, rather, from a spacious and relaxed state of well-being, which allows them to see people and situations more clearly, but also to maintain a basic sense of happiness regardless of their personal circumstances.

In fact, we often hear of rich, famous, or otherwise influential people who are one day forced to acknowledge that their achievements haven’t given them the happiness they expected. In spite of their wealth and power, they swim in an ocean of pain, which is sometimes so deep that suicide seems the only escape. Such intense pain results from believing that objects or situations can create lasting happiness.

If you truly want to discover a lasting sense of peace and contentment, you need to learn to rest your mind. Only by resting the mind can its innate qualities be revealed. The simplest way to clear water obscured by mud and other sediments is to allow the water to grow still. In the same way, if you allow the mind to come to rest, ignorance, attachment, aversion, and all other mental afflictions will gradually settle, and the compassion, clarity, and infinite expanse of your mind’s real nature will be revealed.

MUA THỈNH KINH SÁCH PHẬT HỌC

DO NXB LIÊN PHẬT HỘI PHÁT HÀNH

Mua sách qua Amazon sẽ được gửi đến tận nhà - trên toàn nước Mỹ, Canada, Âu châu và Úc châu.

Quý vị đang truy cập từ IP 216.73.216.110 và chưa ghi danh hoặc đăng nhập trên máy tính này. Nếu là thành viên, quý vị chỉ cần đăng nhập một lần duy nhất trên thiết bị truy cập, bằng email và mật khẩu đã chọn.

Chúng tôi khuyến khích việc ghi danh thành viên ,để thuận tiện trong việc chia sẻ thông tin, chia sẻ kinh nghiệm sống giữa các thành viên, đồng thời quý vị cũng sẽ nhận được sự hỗ trợ kỹ thuật từ Ban Quản Trị trong quá trình sử dụng website này.

Việc ghi danh là hoàn toàn miễn phí và tự nguyện.

Ghi danh hoặc đăng nhập

... ...

Trang chủ

Trang chủ