Khi bạn dấn thân hoàn thiện các nhu cầu của tha nhân, các nhu cầu của bạn cũng được hoàn thiện như một hệ quả.Đức Đạt-lai Lạt-ma XIV

Tinh cần giữa phóng dật, tỉnh thức giữa quần mê. Người trí như ngựa phi, bỏ sau con ngựa hènKinh Pháp cú (Kệ số 29)

Hạnh phúc đích thực không quá đắt, nhưng chúng ta phải trả giá quá nhiều cho những thứ ta lầm tưởng là hạnh phúc. (Real happiness is cheap enough, yet how dearly we pay for its counterfeit.)Hosea Ballou

Cuộc sống là một sự liên kết nhiệm mầu mà chúng ta không bao giờ có thể tìm được hạnh phúc thật sự khi chưa nhận ra mối liên kết ấy.Tủ sách Rộng Mở Tâm Hồn

Nỗ lực mang đến hạnh phúc cho người khác sẽ nâng cao chính bản thân ta. (An effort made for the happiness of others lifts above ourselves.)Lydia M. Child

Hành động thiếu tri thức là nguy hiểm, tri thức mà không hành động là vô ích. (Action without knowledge is dangerous, knowledge without action is useless. )Walter Evert Myer

Ngay cả khi ta không tin có thế giới nào khác, không có sự tưởng thưởng hay trừng phạt trong tương lai đối với những hành động tốt hoặc xấu, ta vẫn có thể sống hạnh phúc bằng cách không để mình rơi vào sự thù hận, ác ý và lo lắng. (Even if (one believes) there is no other world, no future reward for good actions or punishment for evil ones, still in this very life one can live happily, by keeping oneself free from hatred, ill will, and anxiety.)Lời Phật dạy (Kinh Kesamutti)

Mất lòng trước, được lòng sau. (Better the first quarrel than the last.)Tục ngữ

Phán đoán chính xác có được từ kinh nghiệm, nhưng kinh nghiệm thường có được từ phán đoán sai lầm. (Good judgment comes from experience, and often experience comes from bad judgment. )Rita Mae Brown

Kẻ không biết đủ, tuy giàu mà nghèo. Người biết đủ, tuy nghèo mà giàu. Kinh Lời dạy cuối cùng

Cái hại của sự nóng giận là phá hoại các pháp lành, làm mất danh tiếng tốt, khiến cho đời này và đời sau chẳng ai muốn gặp gỡ mình.Kinh Lời dạy cuối cùng

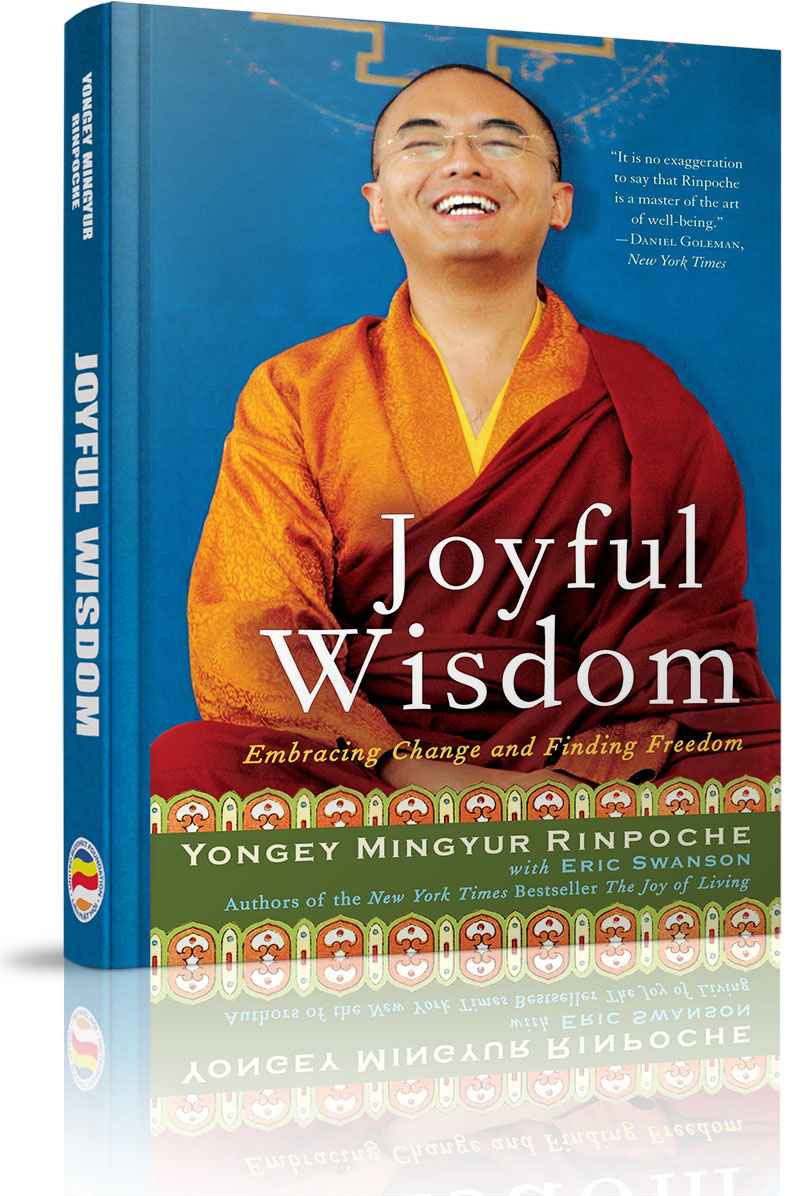

Trang chủ »» Danh mục »» THUYẾT GIẢNG GIÁO PHÁP »» Joyful Wisdom »» Introduction »»

Joyful Wisdom

»» Introduction

Xem Mục lục

Xem Mục lục  Vietnamese || Đối chiếu song ngữ

Vietnamese || Đối chiếu song ngữ

- »» Introduction

- Part One: Principles - 1. Light in the tunnel

- 2. The problem is the solution

- 3. The power of perspective

- 4. The turning point

- 5. Breaking through

- Part Two: Experience - 6. Tools of transformation

- 7. Attention

- 8. Insight

- 9. Empathy

- Part Three: Application – 10. Life on the path

- 11. Making it personal

- 12. Joyful wisdom

- none

ALBERT EINSTEIN

ON A RECENT teaching tour of North America, I was told by a student that an influential philosopher of the twentieth century had called the era in which we live the “age of anxiety.”

“Why?” I asked him.

He explained to me that, according to this philosopher, two bloody world wars had left a kind of emotional scar in people's minds. Never before had so many people been killed in warfare— and worse, the high death toll was a direct result of industrial and scientific advances that were supposed to have made human life more civilized and comfortable.

Since those terrible wars, he went on to say, nearly every advance we've made in terms of material comfort and convenience has had a shadow side. The same technological breakthroughs that have given us cell phones, supermarket scanners, ATMs, and personal computers are the basis for creating weapons that can wipe out entire populations and perhaps destroy the planet we call home. E-mail, the Internet, and other computer technologies that were supposed to make our lives easier often overwhelm us with too much information and too many possibilities, all supposedly urgent, demanding our attention.

The news we hear, he continued—online, in magazines and newspapers, or on TV-is overwhelmingly unpleasant: full of crises, violent images, and predictions of worse to come. I asked him why these reports focus so much on violence, crime, and terrorism rather than on the good deeds that people have done and the successes that people have accomplished.

“Bad news sells,” he replied.

I didn't understand that phrase, and asked him what he meant.

“Disasters get people's attention,” he explained. “People are drawn to bad news because it confirms our worst fears that life is unpredictable and scary. We're always on the lookout for the next terrible thing so we can perhaps prepare against it—whether it's a stock market crash, a suicide bomb, a tidal wave, or an earthquake. 'Aha,' we think, 'I was right to be scared . . . now let me think about what I can do to protect myself.'“

As I listened to him, I realized that the emotional climate he was describing wasn't at all unique to the modern age. From the twenty-five-hundred-year-old perspective of Buddhism, every chapter in human history could be described as an “age of anxiety.” The anxiety we feel now has been part of the human condition for centuries. In general, we respond to this basic unease and the disturbing emotions that arise from it in two distinct ways. We try to escape or we succumb. Either route often ends up creating more complications and problems in our lives.

Buddhism offers a third option. We can look directly at the disturbing emotions and other problems we experience in our lives as stepping-stones to freedom. Instead of rejecting them or surrendering to them, we can befriend them, working through them to reach an enduring, authentic experience of our inherent wisdom, confidence, clarity, and joy.

“How do I apply this approach?” many people ask. “How do I take my life on the path?” This book is, in many ways, a response to their questions: a practical guide to applying the insights and practices of Buddhism to the challenges of everyday life.

It's also meant for people who may not be experiencing any problems or difficulties at the moment; people whose lives are proceeding quite happily and contentedly. For these fortunate individuals it serves as an examination of the basic conditions of human life from a Buddhist perspective that may prove useful, if only as a means of discovering and cultivating a potential of which they might not even be aware.

In some ways, it would be easy just to organize the ideas and methods discussed in the following pages as a simple instruction manual—the kind of pamphlet you get when you buy a cell phone, for instance. “Step One: Check to make sure that the package includes all of the following . . .” “Step Two: Remove the battery cover on the back of the phone.” “Step Three: Insert the battery.”

But I was trained in a very traditional fashion, and it was instilled in me from a young age that a basic understanding of the principles—what we might call the view—was essential in order to derive any real benefit from practice. We have to understand our basic situation in order to work with it. Otherwise, our practice goes nowhere; we're just flailing around blindly without any sense of direction or purpose.

For this reason, it seemed to me that the best approach would be to organize the material into three parts, following the pattern of classical Buddhist texts. Part One explores our basic situation: the nature and causes of the various forms of unease that condition our lives and their potential to guide us toward a profound recognition of our own nature. Part Two offers a step-by-step guide through three basic meditation practices aimed at settling our minds, opening our hearts, and cultivating wisdom. Part Three is devoted to applying the understanding gained in Part One and the methods described in Part Two to common emotional, physical, and personal problems.

While my own early struggles may contribute in some small way to the topics explored in the following pages, a far greater share of insight has come from my teachers and friends. I owe a special debt of gratitude, however, to the people I've met over the past twelve years of teaching around the world, who have spoken so candidly about their own lives. The stories they've told me have broadened my understanding of the complexities of emotional life and deepened my appreciation of the tools I learned as a Buddhist.

MUA THỈNH KINH SÁCH PHẬT HỌC

DO NXB LIÊN PHẬT HỘI PHÁT HÀNH

Mua sách qua Amazon sẽ được gửi đến tận nhà - trên toàn nước Mỹ, Canada, Âu châu và Úc châu.

Quý vị đang truy cập từ IP 216.73.216.215 và chưa ghi danh hoặc đăng nhập trên máy tính này. Nếu là thành viên, quý vị chỉ cần đăng nhập một lần duy nhất trên thiết bị truy cập, bằng email và mật khẩu đã chọn.

Chúng tôi khuyến khích việc ghi danh thành viên ,để thuận tiện trong việc chia sẻ thông tin, chia sẻ kinh nghiệm sống giữa các thành viên, đồng thời quý vị cũng sẽ nhận được sự hỗ trợ kỹ thuật từ Ban Quản Trị trong quá trình sử dụng website này.

Việc ghi danh là hoàn toàn miễn phí và tự nguyện.

Ghi danh hoặc đăng nhập

... ...

Trang chủ

Trang chủ