Nếu bạn không thích một sự việc, hãy thay đổi nó; nếu không thể thay đổi sự việc, hãy thay đổi cách nghĩ của bạn về nó. (If you don’t like something change it; if you can’t change it, change the way you think about it. )Mary Engelbreit

Không làm các việc ác, thành tựu các hạnh lành, giữ tâm ý trong sạch, chính lời chư Phật dạy.Kinh Đại Bát Niết-bàn

Nếu bạn không thích một sự việc, hãy thay đổi nó; nếu không thể thay đổi sự việc, hãy thay đổi cách nghĩ của bạn về nó. (If you don’t like something change it; if you can’t change it, change the way you think about it. )Mary Engelbreit

Đừng cư xử với người khác tương ứng với sự xấu xa của họ, mà hãy cư xử tương ứng với sự tốt đẹp của bạn. (Don't treat people as bad as they are, treat them as good as you are.)Khuyết danh

Chấm dứt sự giết hại chúng sinh chính là chấm dứt chuỗi khổ đau trong tương lai cho chính mình.Tủ sách Rộng Mở Tâm Hồn

Hạnh phúc là khi những gì bạn suy nghĩ, nói ra và thực hiện đều hòa hợp với nhau. (Happiness is when what you think, what you say, and what you do are in harmony.)Mahatma Gandhi

Điểm yếu nhất của chúng ta nằm ở sự bỏ cuộc. Phương cách chắc chắn nhất để đạt đến thành công là luôn cố gắng thêm một lần nữa [trước khi bỏ cuộc]. (Our greatest weakness lies in giving up. The most certain way to succeed is always to try just one more time. )Thomas A. Edison

Nếu quyết tâm đạt đến thành công đủ mạnh, thất bại sẽ không bao giờ đánh gục được tôi. (Failure will never overtake me if my determination to succeed is strong enough.)Og Mandino

Lo lắng không xua tan bất ổn của ngày mai nhưng hủy hoại bình an trong hiện tại. (Worrying doesn’t take away tomorrow’s trouble, it takes away today’s peace.)Unknown

Cuộc đời là một tiến trình học hỏi từ lúc ta sinh ra cho đến chết đi. (The whole of life, from the moment you are born to the moment you die, is a process of learning. )Jiddu Krishnamurti

Sự thành công thật đơn giản. Hãy thực hiện những điều đúng đắn theo phương cách đúng đắn và vào đúng thời điểm thích hợp. (Success is simple. Do what's right, the right way, at the right time.)Arnold H. Glasow

Trang chủ »» Danh mục »» TỦ SÁCH RỘNG MỞ TÂM HỒN »» none »» X. ESTABLISHING AN EQUITABLE SOCIETY »»

none

»» X. ESTABLISHING AN EQUITABLE SOCIETY

Xem Mục lục

Xem Mục lục  Vietnamese || Đối chiếu song ngữ

Vietnamese || Đối chiếu song ngữ

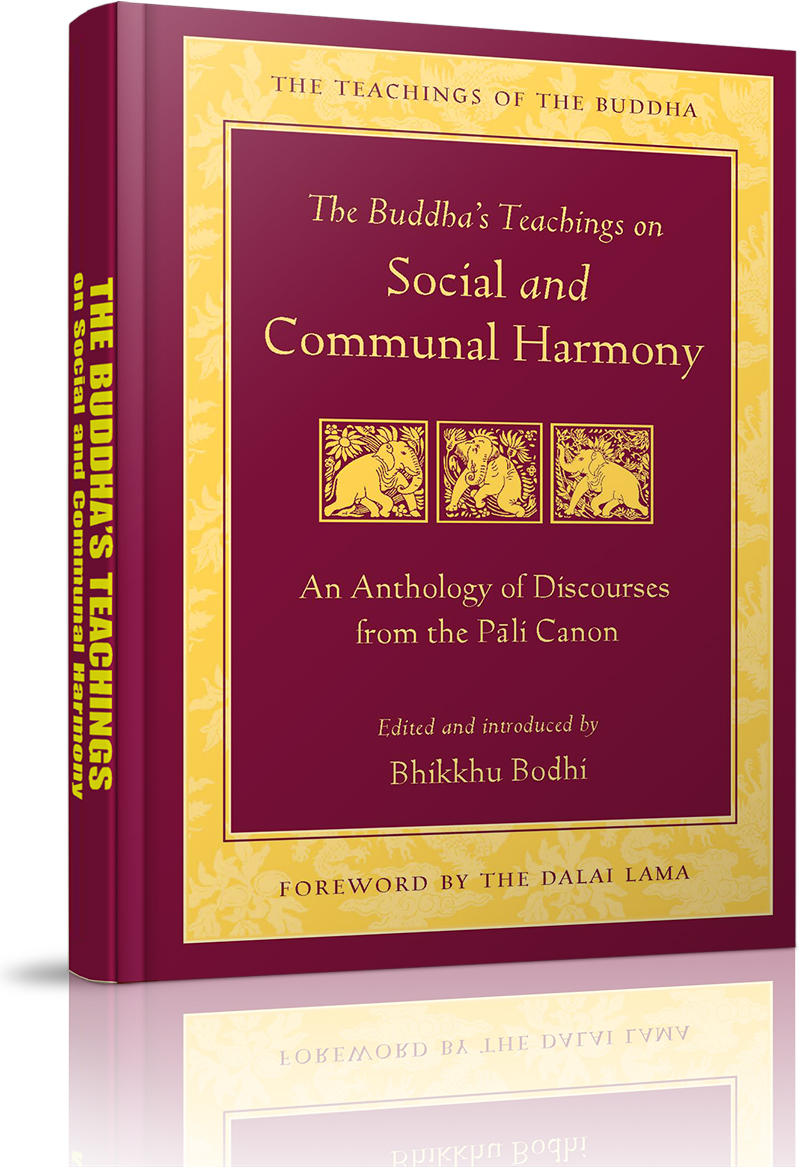

- About Bhikkhu Bodhi

- Foreword by His Holiness The Dalai Lama

- none

- General Introduction

- I. RIGHT UNDERSTANDING

- II. PERSONAL TRAINING

- III. DEALING WITH ANGER

- IV. PROPER SPEECH

- V. GOOD FRIENDSHIP

- VI. ONE’S OWN GOOD AND THE GOOD OF OTHERS

- VII. THE INTENTIONAL COMMUNITY

- VIII. DISPUTES

- IX. SETTLING DISPUTES

- »» X. ESTABLISHING AN EQUITABLE SOCIETY

- Epilogue BY HOZAN ALAN SENAUKE

In the last part of this anthology, we move from the intentional community to the natural community, proceeding from the family to the larger society and then to the state. The texts included here reveal the pragmatic astuteness of the Buddha’s wisdom, his ability to address practical issues with uncanny insight and directness. Although he had adopted the life of a samaṇa, a renunciant who stood outside all social institutions, from the distance he looked back into the social institutions of his time and suggested ideals and arrangements to promote the spiritual, psychological, and physical well-being of people still immersed in the confines of the world. He apparently saw the key to a healthy society to lie in the fulfillment of one’s responsibilities toward others. He regarded the social order as a tapestry of overlapping and intersecting relationships each of which imposed on people duties with respect to those at the other pole of each relationship in which they participated.

This point comes through most saliently in Text X,1, an excerpt from a discourse given to a young man named Sīgalaka. The Buddha here treats society as constituted by six paired relationships: parents and children, husbands and wives, friends with each other, employers and employees, teachers and students, and religious teachers and lay supporters. For each the Buddha proposed five (or in one case six) duties that each should fulfill toward the others. He sees the individual — every individual — as standing at a point where the “six directions” converge, and thus obliged to honor these directions by performing the duties inherent in the relationship.

The Buddha regarded the family as the basic unit of social integration and acculturation. It is especially the close, loving relationship between parents and children that nurtures the virtues and sense of humane responsibility essential to a cohesive social order. Within the family, these values are transmitted from one generation to the next, and thus a harmonious society is highly dependent on cordial and respectful relations between parents and children. In Text X,2(1) he explains how parents are of great benefit to their children, and in X,2(2) he says that one’s parents can never be adequately repaid by conferring material benefits on them but only by establishing them in faith, virtuous conduct, generosity, and wisdom. Wholesome relations between parents and children depend in turn on the mutual affection and respect of husband and wife. The discourse selected for Text X,3 offers guidelines for proper relationships between married couples, holding that the ideal marriage is one in which both husband and wife share a commitment to virtuous conduct, generosity, and spiritual values.

In the next section I have collected texts that deal with the social behavior of the householder. The first two, Texts X,4(1)–(2), affirm that the devout householder arises for the welfare of many and leads his family members in the development of faith, virtue, learning, generosity, and wisdom. Text X,4(3) discusses the proper ways of seeking wealth, which must take place within the strictures of right livelihood. The spiritual dimension enters by asserting that the householder uses wealth “without being tied to it, infatuated with it, and blindly absorbed in it.” Text X,4(4) speaks of five trades that are prohibited for the earnest lay disciple, prohibited because they involve harm, either actual or potential, for other living beings. Text X,4(5) then explains five proper ways of using wealth. The explanation shows that wealth rightly earned is to be used for both self-benefit and the benefit of others; after one has secured the well-being of oneself and one’s family, one is to use the wealth primarily to perform meritorious deeds that are of service to others.

The next section brings us back to the issue of caste, touched on from a monastic perspective in Part VII. Contrary to a common belief, the Buddha did not openly advocate for the abolition of the caste system, which in his time had not yet acquired the complexity and rigidity it acquired in later centuries, primarily as formulated in the Hindu law books. Perhaps he saw that social divisions and the different responsibilities they entailed were inevitable. But he did reject claims about the sanctity of the caste system on several grounds, theological, moral, and spiritual. Theologically, he repudiated the brahmin claim that the castes were created by Brahmā, the creator god; instead he regarded the system as a mere social institution of purely human origin. Morally, he rejected the belief that caste status was indicative of moral worth, with superior moral status inhering in those of the higher castes. Instead he held that it was one’s deeds that determined one’s moral worth, and that anyone from any social class who engaged in unwholesome deeds would lower their moral status and anyone who engaged in wholesome deeds would elevate their moral status. And spiritually, as we saw earlier, he held that anyone from any caste could practice the Dhamma and attain the ultimate goal.

These arguments are presented here in Texts X,5(1)–(4). The conversations recorded in these discourses — in which the caste structure is treated as a model the brahmins seek to impose on society — suggest that in northeast India, where Buddhism arose, caste stratification had not reached the degree of rigidity and authoritativeness that it may have reached in western and central India. It is also interesting to note that when listing the castes in sequence, where the brahmins put themselves on top and the khattiyas beneath them, the Buddha puts the khattiyas on top and the brahmins in second place. In this respect, he may have been following the convention that prevailed in the northeastern states of the subcontinent.

In X,5(1) the Buddha argues against the brahmin claim, advanced by the brahmin Esukārī, that society should be ordered according to a fixed hierarchy of service, such that everyone in the lower castes must serve the brahmins, while the suddas, at the bottom of the caste ladder, must serve everyone else. The Buddha, in contrast, holds that service should be based on the opportunities offered for one’s moral advancement. The brahmin Esukārī also maintains that those in each caste have their own fixed duty that follows from their caste status; this seems to be a precursor of the theory of svadharma that became prominent in the Hindu law books, the idea that each caste has its own duties that one must fulfill if one is to reap a better rebirth and progress toward final liberation. Again, the Buddha rejects this view, holding that the “supramundane Dhamma” is the natural wealth of every person. Whoever observes the principles of good conduct, regardless of caste background, is cultivating “the Dhamma that is wholesome.”

In Text X,5(2), the monk Mahākaccāna, who was himself of brahmin stock, argues against the brahmin claim that the caste system is of divine origins and that the brahmins alone are “the sons of Brahmā, the offspring of Brahmā.” He maintains instead that “this is just a saying in the world.” The caste system is purely conventional, and those from any caste may prove themselves morally worthy or morally defective. In X,5(3)–(4) the Buddha again rejects the idea that caste status is determined by birth and proposes redefinitions of the concepts of brahmin and outcast, respectively, whereby they are defined not by birth but by a person’s own moral character.

The next section briefly looks at the Buddha’s political vision. In his time, the Indian subcontinent was divided into sixteen states, which were of two types: tribal republics and monarchies. We already saw an example of the Buddha’s advice to the republican leaders in Text VII,3(4), on the seven conditions for non-decline that he taught to the Vajjis. However, the northern region of India was rapidly undergoing a tectonic transition that was overturning the prevailing political order. The kingships of several states were expanding and swallowing up weaker kingdoms and the small republics, whose days seemed numbered. Competing claims for territory and wealth led to a rise in militarism and violent clashes. The region was rapidly heading toward an era of ruthless power struggles and vicious wars of aggression poignantly depicted in the following verse (SN 1:28, CDB 103):

Those of great wealth and property,

even khattiyas who rule the country,

look at each other with greedy eyes,

insatiable in sensual pleasures.

Since the triumph of the monarchical type of government appeared inevitable, the Buddha sought to safeguard against abuses of power by positing a model of kingship that would subordinate the king to a higher authority, an objective standard of goodness that could curb the arbitrary exercise of power. He realized that in a monarchical political system, the whole society follows the example set by its ruler, whether for good or bad. Thus in Text X,6(1) he describes the role of the king, ascribing an almost mystical potency to the influence of the ruler’s conduct on his realm. In an age of military struggles over territory, he condemned the resort to war as a means of resolving conflicts. Text X,6(2) states that victory only breeds enmity and maintains the cycle of retaliation. The Jātakas, the stories of the Buddha’s past lives, further summarize the qualities expected in a righteous ruler with a scheme of ten royal virtues: giving, moral conduct, relinquishment, honesty, gentleness, personal austerity, non-anger, non-injury, patience, and non-opposition to the will of the people.1 The Kukka Jātaka, for example, describes the virtuous king as one who “following these ten royal virtues, ruling in accordance with the Dhamma, brings about prosperity and progress for himself and others without troubling anyone” (Jātakas III 320).

To ensure that kings had an exemplary standard of rulership to emulate, the Buddha established the ideal of the “wheel-turning monarch” (rājā cakkavattī), the righteous king who rules in compliance with the Dhamma, the impersonal law of righteousness. The wheel-turning monarch is the secular counterpart of the Buddha; for both, the wheel is the symbol of their authority. As Text X,6(3) shows, the Dhamma that the wheel-turning monarch obeys is the ethical justification for his rule. He extends protection to all in his realm, to people from every walk of life and even to the birds and beasts. Symbolized by the sacred wheel-treasure, the law of righteousness enables the king to peaceably conquer the world and establish a universal reign of peace based on observance of the five precepts and the ten courses of wholesome action, as described in Text X,6(4).

Among the monarch’s duties is to prevent crime from proliferating in his kingdom, and to keep the kingdom safe from crime he must give wealth to those in need. In Early Buddhism, poverty is regarded as the breeding ground of criminality and the alleviation of poverty thus becomes one of the royal duties. This duty is mentioned among the obligations of a wheel-turning monarch in Text X,6(5), which shows how, from the failure to alleviate poverty, all manner of moral depravities arise: theft, murder, lying, and other transgressions. The king’s obligation to relieve poverty is elaborated in X,6(6). Here, in a story purportedly referring to the distant past, a wise chaplain — who is none other than the Buddha in a previous birth — advises the king that the proper way to end the theft and brigandage plaguing his realm is not by imposing harsher punishments and stricter law enforcement but by giving the citizens the means they need to earn a decent living. Once the people enjoy a satisfactory standard of living, they lose all interest in harming others and the country enjoys peace and tranquility.

X. Establishing an Equitable Society

1. RECIPROCAL RESPONSIBILITIES

[The Buddha is speaking to a young man named Sīgalaka:]

“And how, young man, does the noble disciple protect the six directions? These six things are to be regarded as the six directions. The east denotes mother and father. The south denotes teachers. The west denotes wife and children. The north denotes friends and companions. The nadir denotes servants, workers, and helpers. The zenith denotes ascetics and brahmins.

“There are five ways in which a son should minister to his mother and father as the eastern direction. [He should think:] ‘Having been supported by them, I will support them. I will perform their duties for them. I will keep up the family tradition. I will be worthy of my heritage. After my parents’ deaths I will distribute gifts on their behalf.’ And there are five ways in which the parents, so ministered to by their son as the eastern direction, will reciprocate: they will restrain him from evil, support him in doing good, teach him some skill, find him a suitable wife, and, in due time, hand over his inheritance to him. In this way the eastern direction is covered, making it secure and free from peril.

“There are five ways in which pupils should minister to their teachers as the southern direction: by rising to greet them, by waiting on them, by being attentive, by serving them, by mastering the skills they teach. And there are five ways in which their teachers, thus ministered to by their pupils as the southern direction, will reciprocate: they will give thorough instruction, make sure they have grasped what they should have duly grasped, give them a thorough grounding in all skills, recommend them to their friends and colleagues, and provide them with security in all directions. In this way the southern direction is covered, making it secure and free from peril.

“There are five ways in which a husband should minister to his wife as the western direction: by honoring her, by not disparaging her, by not being unfaithful to her, by giving authority to her, by providing her with adornments. And there are five ways in which a wife, thus ministered to by her husband as the western direction, will reciprocate: by properly organizing her work, by being kind to the servants, by not being unfaithful, by protecting stores, and by being skillful and diligent in all she has to do. In this way the western direction is covered, making it secure and free from peril.

“There are five ways in which a man should minister to his friends and companions as the northern direction: by gifts, by kindly words, by looking after their welfare, by treating them like himself, and by keeping his word. And there are five ways in which friends and companions, thus ministered to by a man as the northern direction, will reciprocate: by looking after him when he is inattentive, by looking after his property when he is inattentive, by being a refuge when he is afraid, by not deserting him when he is in trouble, and by showing concern for his children. In this way the northern direction is covered, making it secure and free from peril.

“There are five ways in which a master should minister to his servants and workers as the nadir: by arranging their work according to their strength, by supplying them with food and wages, by looking after them when they are ill, by sharing special delicacies with them, and by letting them off work at the right time. And there are five ways in which servants and workers, thus ministered to by their master as the nadir, will reciprocate: they will get up before him, go to bed after him, take only what they are given, do their work properly, and be bearers of his praise and good repute. In this way the nadir is covered, making it secure and free from peril.

“There are five ways in which a man should minister to ascetics and brahmins as the zenith: by kindness in bodily deed, speech, and thought, by keeping open house for them, and by supplying their bodily needs. And the ascetics and brahmins, thus ministered to by him as the zenith, will reciprocate in six ways: they will restrain him from evil, enjoin him in the good, be compassionate toward him, teach him what he has not learned, clarify what he has learned, and point out to him the way to heaven. In this way the zenith is covered, making it secure and free from peril.”

(from DN 31, LDB 466–68)

2. PARENTS AND CHILDREN

(1) Parents Are of Great Help

“Monks, those families dwell with Brahmā where at home the parents are respected by their children. Those families dwell with the ancient teachers where at home the parents are respected by their children. Those families dwell with the ancient deities where at home the parents are respected by the children. Those families dwell with the holy ones where at home the parents are respected by their children.

“‘Brahmā,’ monks, is a term for father and mother. ‘The ancient teachers’ is a term for father and mother. ‘The ancient deities’ is a term for father and mother. ‘The holy ones’ is a term for father and mother. And why? Parents are of great help to their children; they bring them up, feed them, and show them the world.”

(AN 4:63, NDB 453)

(2) Repaying One’s Parents

“Monks, I declare that there are two persons that are not easily repaid. What two? One’s mother and father.

Even if one should carry about one’s mother on one shoulder and one’s father on the other, and while doing so should live a hundred years, reach the age of a hundred years; and if one should attend to them by anointing them with balms, by massaging, bathing, and rubbing their limbs, and they should even void their excrements there — even by that one would not do enough for one’s parents, nor would one repay them. Even if one were to establish one’s parents as the supreme lords and rulers over this earth so rich in the seven treasures, one would not do enough for them, nor would one repay them. For what reason? Parents are of great help to their children; they bring them up, feed them, and show them the world.

But one who encourages his unbelieving parents, settles and establishes them in faith; who encourages his immoral parents, settles and establishes them in moral virtue; who encourages his miserly parents, settles and establishes them in generosity; who encourages his ignorant parents, settles and establishes them in wisdom — such a one does enough for his parents: he repays them and more than repays them for what they have done.”

(AN 2:33, NDB 153–54)

3. HUSBANDS AND WIVES

On one occasion the Blessed One was traveling along the highway between Madhurā and Verañjā, and a number of householders and their wives were traveling along the same road. Then the Blessed One left the road and sat down on a seat at the foot of a tree. The householders and their wives saw the Blessed One sitting there and approached him. Having paid homage to him, they sat down to one side, and the Blessed One then said to them:

“Householders, there are these four kinds of marriages. What four? A wretch lives together with a wretch; a wretch lives together with a goddess; a god lives together with a wretch; a god lives together with a goddess.

“And how does a wretch live together with a wretch? Here, householders, the husband is one who destroys life, takes what is not given, engages in sexual misconduct, speaks falsely, and indulges in wines, liquor, and intoxicants, the basis for negligence; he is immoral, of bad character; he dwells at home with a heart obsessed by the stain of miserliness; he abuses and reviles ascetics and brahmins. And his wife is exactly the same in all respects. It is in such a way that a wretch lives together with a wretch.

“And how does a wretch live together with a goddess? Here, householders, the husband is one who destroys life . . . who abuses and reviles ascetics and brahmins. But his wife is one who abstains from the destruction of life . . . from wines, liquor, and intoxicants; she is virtuous, of good character; she dwells at home with a heart free from the stain of miserliness; she does not abuse or revile ascetics and brahmins. It is in such a way that a wretch lives together with a goddess.

“And how does a god live together with a wretch? Here, householders, the husband is one who abstains from the destruction of life . . . who does not abuse or revile ascetics and brahmins. But his wife is one who destroys life . . . who abuses and reviles ascetics and brahmins. It is in such a way that a god lives together with a wretch.

“And how does a god live together with a goddess? Here, householders, the husband is one who abstains from the destruction of life . . . from wines, liquor, and intoxicants; he is virtuous, of good character; he dwells at home with a heart free from the stain of miserliness; he does not abuse or revile ascetics and brahmins. And his wife is exactly the same in all respects. It is in such a way that a god lives together with a goddess.

“These, householders, are the four kinds of marriages.”

(AN 4:53, NDB 443–44)

4. THE HOUSEHOLD

(1) For the Welfare of Many

“Monks, when a good person is born in a family, it is for the good, welfare, and happiness of many people. It is for the good, welfare, and happiness of (1) his mother and father, (2) his wife and children, (3) his servants, workers, and helpers, (4) his friends and companions, and (5) ascetics and brahmins.

Just as a great rain cloud, nurturing all the crops, appears for the good, welfare, and happiness of many people, so too, when a good person is born in a family, it is for the good, welfare, and happiness of many people. It is for the good, welfare, and happiness of his mother and father . . . ascetics and brahmins.”

(AN 5:42, NDB 667)

(2) Like the Himalayas

“Monks, based on the Himalayas, the king of mountains, great sal trees grow in five ways. What five? (1) They grow in branches, leaves, and foliage; (2) they grow in bark; (3) they grow in shoots; (4) they grow in softwood; and (5) they grow in heartwood. Based on the Himalayas, the king of mountains, great sal trees grow in these five ways. So too, when the family head is endowed with faith, the people in the family who depend on him grow in five ways. What five? (1) They grow in faith; (2) they grow in virtuous behavior; (3) they grow in learning; (4) they grow in generosity; and (5) they grow in wisdom. When the head of a family is endowed with faith, the people in the family who depend on him grow in these five ways.”

(AN 5:40, NDB 664)

(3) Ways of Seeking Wealth

“The householder who seeks wealth righteously, without violence, and makes himself happy and pleased, and shares it and does meritorious deeds, and uses that wealth without being tied to it, infatuated with it, and blindly absorbed in it, seeing the danger in it and understanding the escape — he may be praised on four grounds. The first ground on which he may be praised is that he seeks wealth righteously, without violence. The second ground on which he may be praised is that he makes himself happy and pleased. The third ground on which he may be praised is that he shares the wealth and does meritorious deeds. The fourth ground on which he may be praised is that he uses that wealth without being tied to it, infatuated with it, and blindly absorbed in it, seeing the danger in it and understanding the escape. This householder may be praised on these four grounds.

“Just as from a cow comes milk, from milk curd, from curd butter, from butter ghee, and from ghee comes cream-of-ghee, which is reckoned the foremost of all these, so among all householders, the foremost, the best, the preeminent, the supreme, and the finest is the one who seeks wealth righteously, without violence; and having done so, makes himself happy and pleased; and shares the wealth and does meritorious deeds; and uses that wealth without being tied to it, infatuated with it, and blindly absorbed in it, seeing the danger in it and understanding the escape.”

(from AN 10:91, NDB 1461; see too SN 42:12, CDB 1356)

(4) Avoiding Wrong Livelihood

“Monks, a lay follower should not engage in these five trades. What five? Trading in weapons, trading in living beings, trading in meat, trading in intoxicants, and trading in poisons. A lay follower should not engage in these five trades.”

(AN 5:177, NDB 790)

(5) The Proper Use of Wealth

The Blessed One said to the householder Anāthapiṇḍika: “Householder, there are these five utilizations of wealth. What are the five?

(1) “Here, householder, with wealth acquired by energetic striving, amassed by the strength of his arms, earned by the sweat of his brow, righteous wealth righteously gained, the noble disciple makes himself happy and pleased and properly maintains himself in happiness; he makes his parents happy and pleased and properly maintains them in happiness; he makes his wife and children, his servants, workers, and helpers happy and pleased and properly maintains them in happiness. This is the first utilization of wealth.

(2) “Again, with wealth acquired by energetic striving . . . righteously gained, the noble disciple makes his friends and companions happy and pleased and properly maintains them in happiness. This is the second utilization of wealth.

(3) “Again, with wealth acquired by energetic striving . . . righteously gained, the noble disciple makes provisions with his wealth against the losses that might arise because of fire or floods, kings or bandits or unloved heirs; he makes himself secure against them. This is the third utilization of wealth.

(4) “Again, with wealth acquired by energetic striving . . . righteously gained, the noble disciple makes the five oblations: to relatives, guests, ancestors, the king, and the deities. This is the fourth utilization of wealth.

(5) “Again, with wealth acquired by energetic striving . . . righteously gained, the noble disciple establishes an uplifting offering of alms — an offering that is heavenly, resulting in happiness, conducive to heaven — to those ascetics and brahmins who refrain from intoxication and heedlessness, who are settled in patience and mildness, who tame themselves, calm themselves, and train themselves for nibbāna. This is the fifth utilization of wealth.”

(AN 5:41, NDB 665–66)

5. SOCIAL STATUS

(1) No Fixed Hierarchy of Privilege

Then the brahmin Esukārī went to the Blessed One and said to him:

“Master Gotama, the brahmins prescribe four levels of service. They prescribe the level of service toward a brahmin, the level of service toward a khattiya, the level of service toward a vessa, and the level of service toward a sudda. The brahmins prescribe this as the level of service toward a brahmin: a brahmin may serve a brahmin, a khattiya may serve a brahmin, a vessa may serve a brahmin, and a sudda may serve a brahmin. They prescribe this as the level of service toward a khattiya: a khattiya may serve a khattiya, a vessa may serve a khattiya, and a sudda may serve a khattiya. They prescribe this as the level of service toward a vessa: a vessa may serve a vessa and a sudda may serve a vessa. They prescribe this as the level of service toward a sudda: only a sudda may serve a sudda; for who else could serve a sudda? What does Master Gotama say about this?”

“Well, brahmin, has all the world authorized the brahmins to prescribe these four levels of service?” – “No, Master Gotama.” – “Suppose, brahmin, they were to force a cut of meat upon a poor, penniless, destitute man and tell him: ‘Good man, you must eat this meat and pay for it’; so too, without the consent of those [other] ascetics and brahmins, the brahmins nevertheless prescribe those four levels of service.

“I do not say, brahmin, that all are to be served, nor do I say that none are to be served. For if, when serving someone, one becomes worse and not better because of that service, then I say that he should not be served. And if, when serving someone, one becomes better and not worse because of that service, then I say that he should be served. . . .

“I do not say, brahmin, that one is better because one is from an aristocratic family, nor do I say that one is worse because one is from an aristocratic family. I do not say that one is better because one is of great beauty, nor do I say that one is worse because one is of great beauty. I do not say that one is better because one is of great wealth, nor do I say that one is worse because one is of great wealth. For one from an aristocratic family may destroy life, take what is not given, engage in sexual misconduct, speak falsely, speak divisively, speak harshly, gossip, be covetous, have a mind of ill will, and hold wrong view. Therefore I do not say that one is better because one is from an aristocratic family. But also one from an aristocratic family may abstain from destroying life, from taking what is not given, from sexual misconduct, from false speech, from divisive speech, from harsh speech, and from idle chatter, and he may be uncovetous, have a benevolent mind, and hold right view. Therefore I do not say that one is worse because one is from an aristocratic family.

“I do not say, brahmin, that all are to be served, nor do I say that none are to be served. For if, when serving someone, one’s faith, virtue, learning, generosity, and wisdom increase in his service, then I say that he should be served.”

The brahmin Esukārī next said to the Blessed One:

“Master Gotama, the brahmins prescribe four types of wealth: the wealth of a brahmin, the wealth of a khattiya, the wealth of a vessa, and the wealth of a sudda. The brahmins prescribe wandering for alms as the wealth of a brahmin; a brahmin who spurns wandering for alms abuses his duty like a guard who takes what has not been given. They prescribe the bow and quiver as the wealth of a khattiya; a khattiya who spurns the bow and quiver abuses his duty like a guard who takes what has not been given. They prescribe agriculture and cattle-breeding as the wealth of a vessa; a vessa who spurns farming and cattle-breeding abuses his duty like a guard who takes what has not been given. They prescribe the sickle and carrying-pole as the wealth of a sudda; a sudda who spurns the sickle and carrying-pole abuses his duty like a guard who takes what has not been given. What does Master Gotama say about this?”

“Well, brahmin, has all the world authorized the brahmins to prescribe these four types of wealth?” – “No, Master Gotama.” – “Suppose, brahmin, they were to force a cut of meat upon a poor, penniless, destitute man and tell him: ‘Good man, you must eat this meat and pay for it’; so too, without the consent of those [other] ascetics and brahmins, the brahmins nevertheless prescribe these four types of wealth.

“Brahmin, I declare the noble supramundane Dhamma as a person’s own wealth. But recollecting his ancient maternal and paternal family lineage, he is reckoned according to wherever he is reborn. If he is reborn in a clan of khattiyas, he is reckoned as a khattiya; if he is reborn in a clan of brahmins, he is reckoned as a brahmin; if he is reborn in a clan of vessas, he is reckoned as a vessa; if he is reborn in a clan of suddas, he is reckoned as a sudda. Just as fire is reckoned by the particular condition dependent on which it burns — when fire burns dependent on logs, it is reckoned as a log fire; when fire burns dependent on faggots, it is reckoned as a faggot fire; when fire burns dependent on grass, it is reckoned as a grass fire; when fire burns dependent on cowdung, it is reckoned as a cowdung fire — so too, brahmin, I declare the noble supramundane Dhamma as a person’s own wealth. But recollecting his ancient maternal and paternal lineage, he is reckoned according to wherever he is reborn.”

(from MN 96, MLDB 786–89)

(2) Caste Is Mere Convention

King Avantiputta of Madhurā asked the Venerable Mahākaccāna:

“Master Kaccāna, the brahmins say thus: ‘Brahmins are the highest caste, those of any other caste are inferior; brahmins are the fairest caste, those of any other caste are dark; only brahmins are purified, not non-brahmins; brahmins alone are the sons of Brahmā, the offspring of Brahmā, born of his mouth, born of Brahmā, created by Brahmā, heirs of Brahmā.’ What does Master Kaccāna say about that?”

“It is just a saying in the world, great king. And there is a way whereby it can be understood how that statement of the brahmins is just a saying in the world. What do you think, great king? If a khattiya prospers in wealth, will there be khattiyas who rise before him and retire after him, who are eager to serve him, who seek to please him and speak sweetly to him, and will there also be brahmins, vessas, and suddas who do likewise?” – “There will be, Master Kaccāna.”

“What do you think, great king? If a brahmin prospers in wealth, will there be brahmins who rise before him and retire after him, who are eager to serve him, who seek to please him and speak sweetly to him, and will there also be vessas, suddas, and khattiyas who do likewise?” – “There will be, Master Kaccāna.”

“What do you think, great king? If a vessa prospers in wealth, will there be vessas who rise before him and retire after him, who are eager to serve him, who seek to please him and speak sweetly to him, and will there also be suddas, khattiyas, and brahmins who do likewise?” – “There will be, Master Kaccāna.”

“What do you think, great king? If a sudda prospers in wealth, will there be suddas who rise before him and retire after him, who are eager to serve him, who seek to please him and speak sweetly to him, and will there also be khattiyas, brahmins, and vessas who do likewise?” – “There will be, Master Kaccāna.”

“What do you think, great king? If that is so, then are these four castes all the same, or are they not, or how does it appear to you in this case?”

“Surely if that is so, Master Kaccāna, then these four castes are all the same: there is no difference between them at all that I see.”

“That is a way, great king, whereby it can be understood how that statement of the brahmins is just a saying in the world.

“What do you think, great king? Suppose a khattiya were to destroy life, take what is not given, engage in sexual misconduct, speak falsely, speak divisively, speak harshly, gossip, be covetous, have a mind of ill will, and hold wrong view. On the dissolution of the body, after death, would he be reborn in a state of misery, in a bad destination, in a lower world, in hell, or not, or how does it appear to you in this case?”

“He would be, Master Kaccāna. That is how it appears to me in this case, and thus I have heard from the arahants.”

“Good, good, great king! What you think is good, great king, and what you have heard from the arahants is good. What do you think, great king? Suppose a brahmin . . . a vessa . . . a sudda were to act likewise?”

“If a brahmin . . . a vessa . . . a sudda were such, Master Kaccāna, he would be reborn in a state of misery, in a bad destination, in a lower world, in hell. That is how it appears to me in this case, and thus I have heard from the arahants.”

“Good, good, great king! What you think is good, great king, and what you have heard from the arahants is good. What do you think, great king? If that is so, then are these four castes all the same, or are they not, or how does it appear to you in this case?”

“Surely if that is so, Master Kaccāna, then these four castes are all the same: there is no difference between them at all that I see.”

“That is also a way, great king, whereby it can be understood how that statement of the brahmins is just a saying in the world.

“What do you think, great king? Suppose a khattiya were to abstain from the destruction of life, from taking what is not given, from sexual misconduct, from false speech, from divisive speech, from harsh speech, and from gossip, and were to be uncovetous, to have a benevolent mind, and to hold right view. On the dissolution of the body, after death, would he be reborn in a good destination, in the heavenly world, or not, or how does it appear to you in this case?”

“He would be, Master Kaccāna. That is how it appears to me in this case, and thus I have heard from the arahants.”

“Good, good, great king! What you think is good, great king, and what you have heard from the arahants is good. What do you think, great king? Suppose a brahmin . . . a vessa . . . a sudda were to abstain from the destruction of life . . . and to hold right view. On the dissolution of the body, after death, would he be reborn in a good destination, in the heavenly world, or not, or how does it appear to you in this case?”

“He would be, Master Kaccāna. That is how it appears to me in this case, and thus I have heard from the arahants.”

“Good, good, great king! What you think is good, great king, and what you have heard from the arahants is good. What do you think, great king? If that is so, then are these four castes all the same, or are they not, or how does it appear to you in this case?”

“Surely if that is so, Master Kaccāna, then these four castes are all the same: there is no difference between them at all that I see.”

“That is also a way, great king, whereby it can be understood how that statement of the brahmins is just a saying in the world.

“What do you think, great king? Suppose a khattiya were to break into houses, plunder wealth, commit burglary, ambush highways, or seduce another’s wife, and if your men arrested him and produced him, saying: ‘Sire, this is the culprit; command what punishment for him you wish,’ how would you treat him?”

“We would have him executed, Master Kaccāna, or we would have him fined, or we would have him exiled, or we would do with him as he deserved. Why is that? Because he has lost his former status of a khattiya and is simply reckoned as a robber.”

“What do you think, great king? Suppose a brahmin . . . a vessa . . . a sudda were to do the same, and if your men arrested him and produced him, saying: ‘Sire, this is the culprit; command what punishment for him you wish,’ how would you treat him?”

“We would have him executed, Master Kaccāna, or we would have him fined, or we would have him exiled, or we would do with him as he deserved. Why is that? Because he has lost his former status of a brahmin . . . a vessa . . . a sudda and is simply reckoned as a robber.”

“What do you think, great king? If that is so, then are these four castes all the same, or are they not, or how does it appear to you in this case?”

“Surely if that is so, Master Kaccāna, then these four castes are all the same; there is no difference between them at all that I see.”

“That is also a way, great king, whereby it can be understood how that statement of the brahmins is just a saying in the world.

“What do you think, great king? Suppose a khattiya, having shaved off his hair and beard, put on the ocher robe, and gone forth from the home life into homelessness, were to abstain from the destruction of life, from taking what is not given, and from false speech. Refraining from eating at night, he would eat only in one part of the day, and would be celibate, virtuous, of good character. How would you treat him?”

“We would pay homage to him, Master Kaccāna, or we would rise up for him, or invite him to be seated; or we would invite him to accept robes, almsfood, lodgings, and medicinal requisites; or we would arrange for him lawful guarding, defense, and protection. Why is that? Because he has lost his former status of a khattiya and is simply reckoned as an ascetic.”

“What do you think, great king? Suppose a brahmin . . . a vessa . . . a sudda were to do the same. How would you treat him?”

“We would pay homage to him, Master Kaccāna, or rise up for him, or invite him to be seated; or we would invite him to accept robes, almsfood, lodgings, and medicinal requisites; or we would arrange for him lawful guarding, defense, and protection. Why is that? Because he has lost his former status of a brahmin . . . a vessa . . . a sudda and is simply reckoned as an ascetic.”

“What do you think, great king? If that is so, then are these four castes all the same, or are they not, or how does it appear to you in this case?”

“Surely if that is so, Master Kaccāna, then these four castes are all the same; there is no difference between them at all that I see.”

“That is also a way, great king, whereby it can be understood how that statement of the brahmins is just a saying in the world.”

(from MN 84, MLDB 698–702)

(3) Status Is Determined by Deeds

[The Buddha is speaking to the young brahmin Vāseṭṭha:]

“While among these many kinds of beings,

their distinctive marks are determined by birth,

among humans there are no distinctive marks

produced by their particular birth.

“Not by the hairs or the head,

not by the ears or by the eyes;

not by the mouth or the nose,

not by the lips or the brows;

“not by the neck or the shoulders,

not by the belly or the back;

not by the buttocks or the breast,

nor by the anus or genitals;

“not by the hands or the feet

nor by the fingers or nails;

not by the knees or the thighs,

nor by their color or voice:

birth does not make a distinctive mark

as it does for the other kinds of beings.

“In human beings with their bodies

nothing distinctive is found.

Classification among human beings

is spoken of by designation.

“The one among humans

who lives by husbandry,

you should know, Vāseṭṭha:

he is a farmer, not a brahmin.

“The one among humans

who earns his living by various crafts,

you should know, Vāseṭṭha:

he is a craftsman, not a brahmin.

“The one among humans

who lives by trade,

you should know, Vāseṭṭha:

he is a merchant, not a brahmin.

“The one among humans

who lives by serving others,

you should know, Vāseṭṭha:

he is a servant, not a brahmin.

“The one among humans

who lives by stealing,

you should know, Vāseṭṭha:

he is a thief, not a brahmin.

“The one among humans

who earns his living by archery,

you should know, Vāseṭṭha:

he is a warrior, not a brahmin.

“The one among humans

who lives by priestly service,

you should know, Vāseṭṭha:

he is a priest, not a brahmin.

“The one among humans

who rules over village and realm,

you should know, Vāseṭṭha:

he is a king, not a brahmin.

“I do not call someone a brahmin

based on genealogy and maternal origin.

He is just a pompous speaker

if he is impeded by things.

One who owns nothing, who takes nothing:

he is the one I call a brahmin.

“One who has cut off all fetters,

who is indeed not agitated,

who has overcome all ties, detached:

he is the one I call a brahmin. . . .

“One who knows his past abodes,

who sees heaven and the plane of misery,

who has reached the destruction of birth:

he is the one I call a brahmin.

“For the name and clan ascribed to one

is a designation in the world.

Having originated by convention,

it is ascribed here and there.

“For those who do not know this,

wrong view has long been their tendency.

Not knowing, they tell us:

‘One is a brahmin by birth.’

“One is not a brahmin by birth,

nor by birth a non-brahmin.

By action one becomes a brahmin,

by action one becomes a non-brahmin.

“One becomes a farmer by action,

by action one becomes a craftsmen.

One becomes a merchant by action,

by action one becomes a servant.

“One becomes a thief by action,

by action one becomes a soldier.

One becomes a priest by action,

by action one becomes a king.

“So that is how the wise

see action as it really is —

seers of dependent origination,

skilled in action and its result.

“By action the world goes round,

by action the population goes round.

Sentient beings are fastened by action

like the linch pin of a moving chariot.

“By austerity, by the spiritual life,

by self-control, by inner taming —

by this one is a brahmin;

this is supreme brahminhood.”

(from MN 98, MLDB 800–807; Sn III,9)

(4) Deeds Make the Outcast

The Blessed One said to the brahmin Aggibhāradvāja:

“Do you know, brahmin, what an outcast is or the qualities that make one an outcast?”

“I do not know, Master Gotama, what an outcast is or the qualities that make one an outcast. Please let Master Gotama teach me the Dhamma in such a way that I might come to know what an outcast is and the qualities that make one an outcast.”

“In that case, brahmin, listen and attend closely. I will speak.”

“Yes, sir,” the brahmin Aggibhāradvāja replied. The Blessed One said this:

“A man who is angry and hostile,

an evil denigrator,

deficient in view, a hypocrite:

you should know him as an outcast.

“One here who injures a living being

whether once-born or twice-born,

who has no kindness toward living beings:

you should know him as an outcast. . . .

“One who extols himself

and despises others,

inferior because of his own conceit:

you should know him as an outcast.

“A scold, stingy,

of evil desires, miserly, a deceiver,

one without moral shame or moral dread:

you should know him as an outcast.

“One who reviles the Buddha

or his disciple,

a wanderer or a householder:

you should know him as an outcast. . . .

“One is not an outcast by birth,

nor by birth is one a brahmin.

By action one becomes an outcast,

by action one becomes a brahmin.”

(from Sn I,7)

6. THE STATE

(1) When Kings Are Unrighteous

“When kings are unrighteous, the royal vassals become unrighteous. When the royal vassals are unrighteous, brahmins and householders become unrighteous. When brahmins and householders are unrighteous, the people of the towns and countryside become unrighteous. When the people of the towns and countryside are unrighteous, the sun and moon proceed off course. When the sun and moon proceed off course, the constellations and the stars proceed off course. When the constellations and the stars proceed off course, day and night proceed off course . . . the months and fortnights proceed off course . . . the seasons and years proceed off course. When the seasons and years proceed off course, the winds blow off course and at random. When the winds blow off course and at random, the deities become upset. When the deities are upset, sufficient rain does not fall. When sufficient rain does not fall, the crops ripen irregularly. When people eat crops that ripen irregularly, they become short-lived, ugly, weak, and sickly.

“But when kings are righteous, the royal vassals become righteous. When the royal vassals are righteous, brahmins and householders become righteous. When brahmins and householders are righteous, the people of the towns and countryside become righteous. When the people of the towns and countryside are righteous, the sun and moon proceed on course. When the sun and moon proceed on course, the constellations and the stars proceed on course. When the constellations and the stars proceed on course, day and night proceed on course . . . the months and fortnights proceed on course . . . the seasons and years proceed on course. When the seasons and years proceed on course, the winds blow on course and dependably. When the winds blow on course and dependably, the deities do not become upset. When the deities are not upset, sufficient rain falls. When sufficient rain falls, the crops ripen in season. When people eat crops that ripen in season, they become long-lived, beautiful, strong, and healthy.”

When cattle are crossing a ford,

if the chief bull goes crookedly,

all the others go crookedly

because their leader has gone crookedly.

So too, among human beings,

when the one considered the chief

behaves unrighteously,

other people do so as well.

The entire kingdom is dejected

if the king is unrighteous.

When cattle are crossing a ford

if the chief bull goes straight across,

all the others go straight across

because their leader has gone straight.

So too, among human beings,

when the one considered the chief

conducts himself righteously,

other people do so as well.

The entire kingdom rejoices

if the king is righteous.

(AN 4:70, NDB 458–59)

(2) War Breeds Enmity

King Ajātasattu of Magadha mobilized a four-division army and marched in the direction of Kāsi against King Pasenadi of Kosala. King Pasenadi heard this report, mobilized a four-division army, and launched a counter-march in the direction of Kāsi against King Ajātasattu. Then King Ajātasattu and King Pasenadi fought a battle, in which King Ajātasattu defeated King Pasenadi. King Pasenadi, defeated, retreated to his own capital of Sāvatthī.

Then, in the morning, a number of monks dressed and, taking their bowls and robes, entered Sāvatthī for alms. When they had walked for alms in Sāvatthī and had returned from their alms round, after the meal they approached the Blessed One and reported what had happened. [The Blessed One said:]

“Monks, King Ajātasattu of Magadha has evil friends. King Pasenadi of Kosala has good friends. Yet for this day, King Pasenadi, having been defeated, will sleep badly tonight.

“Victory breeds enmity,

The defeated one sleeps badly.

The peaceful one sleeps at ease,

Having abandoned victory and defeat.”

[On a later occasion, when Pasenadi defeated Ajātasattu, the Blessed One said:]

“The fool thinks fortune is on his side

so long as his evil does not ripen,

but when the evil ripens

the fool incurs suffering.

“The killer begets a killer,

one who conquers, a conqueror.

The abuser begets abuse,

the reviler, one who reviles.

Thus by the unfolding of kamma

the plunderer is plundered.”

(SN 3:14–15, CDB 177–78)

(3) The Wheel-Turning Monarch

The Blessed One said: “Monks, even a wheel-turning monarch, a just and righteous king, does not govern his realm without a co-regent.”

A certain monk asked: “But who, Bhante, is the co-regent of the wheel-turning monarch, the just and righteous king?”

“It is the Dhamma, the law of righteousness,” replied the Blessed One. “The wheel-turning monarch, the just and righteous king, relying on the Dhamma, honoring the Dhamma, esteeming and respecting it, with the Dhamma as his standard, banner, and sovereign, provides lawful protection, shelter, and safety for his own dependents. He provides lawful protection, shelter, and safety for the khattiyas attending on him; for his army, for the brahmins and householders, for the inhabitants of town and countryside, for ascetics and brahmins, for the beasts and birds. A wheel-turning monarch, a just and righteous king, who thus provides lawful protection, shelter, and safety for all, is the one who rules by Dhamma only. And that rule cannot be overthrown by any hostile human being.”

(from AN 3:14, NDB 208–9)

(4) How a Wheel-Turning Monarch Conquers

“Here, when a head-anointed noble king has bathed his head on the uposatha day of the fifteenth2 and has ascended to the upper palace chamber for the uposatha, there appears to him the divine wheel-treasure with its thousand spokes, its tire, and its nave, complete in every aspect. On seeing it, the head-anointed noble king thinks thus: ‘Now it has been heard by me that when a head-anointed noble king has bathed his head on the uposatha day of the fifteenth and has ascended to the upper palace chamber for the uposatha, and there appears to him the divine wheel-treasure with its thousand spokes, its tire, and its nave, complete in every aspect, then that king becomes a wheel-turning monarch. Am I then a wheel-turning monarch?’

“Then the head-anointed noble king rises from his seat, and taking a water vessel in his left hand, he sprinkles the wheel-treasure with his right hand, saying: ‘Turn forward, good wheel-treasure; triumph, good wheel-treasure!’ Then the wheel-treasure turns forward rolling in the eastern direction and the wheel-turning monarch follows it with his four-constituent army. Now in whatever region the wheel-treasure pauses, there the wheel-turning monarch takes up his abode with his four-constituent army. And opposing kings in the east come to the wheel-turning monarch and speak thus: ‘Come, great king; welcome, great king; command, great king; advise, great king.’ The wheel-turning monarch speaks thus: ‘You should not destroy life; you should not take what has not been given; you should not engage in sexual misconduct; you should not speak falsehood; you should not drink intoxicants; you should enjoy your accustomed enjoyments.’ And the opposing kings in the east submit to the wheel-turning monarch.

“Then the wheel-treasure plunges into the eastern ocean and emerges again. And then it turns forward rolling in the southern direction. . . . And the opposing kings in the south submit to the wheel-turning monarch. Then the wheel-treasure plunges into the southern ocean and emerges again. And then it turns forward rolling in the western direction. . . . And the opposing kings in the west submit to the wheel-turning monarch. Then the wheel-treasure plunges into the western ocean and emerges again. And then it turns forward rolling in the northern direction. . . . And the opposing kings in the north submit to the wheel-turning monarch.

“Now when the wheel-treasure has triumphed over the earth to the ocean’s edge, it returns to the royal capital and remains as if fixed on its axle at the gate of the wheel-turning monarch’s inner palace, as an adornment to the gate of his inner palace. Such is the wheel-treasure that appears to a wheel-turning monarch.”

(from MN 129, MLDB 1023–24; see too DN 26, LDB 397–98)

(5) The Monarch’s Duties

[The Buddha is relating a story of the distant past:] “King Daḷhanemi sent for his eldest son, the crown prince, and said: ‘My son, the sacred wheel-treasure has slipped from its position. And I have heard that when this happens to a wheel-turning monarch, he has not much longer to live. I have had my fill of human pleasures, now is the time to seek heavenly pleasures. You, my son, take over control of this land. I will shave off my hair and beard, put on ocher robes, and go forth from the household life into homelessness.’ And, having installed his eldest son in due form as king, King Daḷhanemi shaved off his hair and beard, put on ocher robes, and went forth from the household life into homelessness. And, seven days after the royal sage had gone forth, the sacred wheel-treasure vanished.

“Then a certain man came to the new king and said: ‘Sire, you should know that the sacred wheel-treasure has disappeared.’ At this the king was grieved and felt sad. He went to his father, the royal sage, and told him the news. And the royal sage said to him: ‘My son, you should not grieve or feel sad at the disappearance of the wheel-treasure. The wheel-treasure is not an heirloom from your fathers. But now, my son, you must turn yourself into a noble wheel-turner. And then it may come about that, if you perform the duties of a noble wheel-turning monarch, on the uposatha day of the fifteenth, when you have washed your head and gone up to the verandah on top of your palace for the uposatha day, the sacred wheel-treasure will appear to you, thousand-spoked, complete with rim, hub, and all accessories.’

“‘But what, Sire, is the duty of a noble wheel-turning monarch?’

“‘It is this, my son: Relying on the Dhamma, honoring the Dhamma, esteeming and respecting it, with the Dhamma as your standard, banner, and sovereign, you should provide lawful protection, shelter, and safety for your own dependents. You should provide lawful protection, shelter, and safety for the khattiyas attending on you; for your army, for the brahmins and householders, for the inhabitants of town and countryside, for ascetics and brahmins, for the beasts and birds. Let no crime prevail in your kingdom, and to those who are in need, give wealth. And whatever ascetics and brahmins in your kingdom have renounced the life of sensual infatuation and are devoted to forbearance and gentleness, each one taming himself, each one calming himself, and each one striving for the end of craving, from time to time you should approach them and ask: “What, Bhante, is wholesome and what is unwholesome, what is blameworthy and what is blameless, what is to be followed and what is not to be followed? What deed will in the long run lead to harm and sorrow, and what to welfare and happiness?” Having listened to them, you should avoid what is unwholesome and do what is wholesome. That, my son, is the duty of a noble wheel-turning monarch.’

“‘Yes, sire,’ he said, and he performed the duties of a noble wheel-turning monarch. And so in succession six subsequent kings arose who became wheel-turning monarchs. Then the seventh king to arise in this dynasty did not go to the royal sage [his father, the former monarch] and ask him about the duties of a wheel-turning monarch. Instead, he ruled the people according to his own ideas, and being so ruled, the people did not prosper so well as they had done under the previous kings who had performed the duties of a wheel-turning monarch.

“The king then ordered all his ministers and advisers to come together, and he consulted them. And they explained to him the duties of a wheel-turning monarch. And having listened to them, the king established guard and protection for his subjects, but he did not give wealth to the needy, and as a result, poverty became rife. Thus, from the not giving of wealth to the needy, poverty became rife. From the growth of poverty, theft increased. From the increase of theft, the use of weapons increased; from the increased use of weapons, the taking of life increased, lying increased, divisive speech increased, and sexual misconduct increased — and on account of this, people’s life- span decreased and their beauty decreased.”

(from DN 26, LDB 396–401, abridged)

(6) Providing for the Welfare of the People

The Blessed One told the brahmin Kūṭadanta:

“Brahmin, once upon a time there was a king called Mahāvijita. He was rich, of great wealth and resources, with an abundance of gold and silver, of possessions and requisites, of money and money’s worth, with a full treasury and granary. And when King Mahāvijita was reflecting in private, the thought came to him: ‘I have acquired extensive wealth in human terms, I occupy a wide extent of land which I have conquered. Let me now make a great sacrifice that would be to my benefit and happiness for a long time.’ And calling his chaplain, he told him his thought. ‘I want to make a great sacrifice. Instruct me, Bhante, how this may be to my lasting benefit and happiness.’

“The chaplain replied: ‘Your Majesty’s country is beset by thieves. It is ravaged; villages and towns are being destroyed; the countryside is infested with brigands. If Your Majesty were to tax this region, that would be the wrong thing to do. Suppose Your Majesty were to think: “I will get rid of this plague of robbers by executions and imprisonment, or by fines, threats, and banishment,” the plague would not be properly ended. Those who survived would later harm Your Majesty’s realm. However, with this plan you can completely eliminate the plague. To those in the kingdom who are engaged in cultivating crops and raising cattle, distribute grain and fodder; to those in trade, give capital; to those in government service, assign proper living wages. Then those people, being intent on their own occupations, will not harm the kingdom. Your Majesty’s revenues will be great; the land will be tranquil and not beset by thieves; and the people, with joy in their hearts, playing with their children, will dwell in open houses.’

“And saying: ‘So be it!,’ the king accepted the chaplain’s advice: he gave grain and fodder to those engaged in cultivating crops and raising cattle, capital to those in trade, proper living wages to those in government service. Then those people, being intent on their own occupations, did not harm the kingdom. The king’s revenues became great; the land was tranquil and not beset by thieves; and the people, with joy in their hearts, playing with their children, dwelt in open houses.”

(from DN 5, LDB 135–36)

MUA THỈNH KINH SÁCH PHẬT HỌC

DO NXB LIÊN PHẬT HỘI PHÁT HÀNH

Mua sách qua Amazon sẽ được gửi đến tận nhà - trên toàn nước Mỹ, Canada, Âu châu và Úc châu.

Quý vị đang truy cập từ IP 216.73.216.215 và chưa ghi danh hoặc đăng nhập trên máy tính này. Nếu là thành viên, quý vị chỉ cần đăng nhập một lần duy nhất trên thiết bị truy cập, bằng email và mật khẩu đã chọn.

Chúng tôi khuyến khích việc ghi danh thành viên ,để thuận tiện trong việc chia sẻ thông tin, chia sẻ kinh nghiệm sống giữa các thành viên, đồng thời quý vị cũng sẽ nhận được sự hỗ trợ kỹ thuật từ Ban Quản Trị trong quá trình sử dụng website này.

Việc ghi danh là hoàn toàn miễn phí và tự nguyện.

Ghi danh hoặc đăng nhập

... ...

Trang chủ

Trang chủ