| |

The Wheel of

Birth and Death

by

Bhikkhu

Khantipalo

The Wheel Publication No. 147/148/149

For free distribution only.

You may print copies of this work for your personal use.

You may re-format and redistribute this work for use on computers and

computer networks,

provided that you charge no fees for its distribution or use.

Otherwise, all rights reserved.

Buddhist Publication Society

P.O. Box 61

54, Sangharaja Mawatha

Kandy, Sri Lanka

Rewritten from an article in

"Visakha Puja" (251), the Annual of the Buddhist Association of

Thailand.

This edition was transcribed from

the print edition in 1995 by Joseph Crea under the auspices of the

DharmaNet Dharma Book Transcription Project, with the kind permission of

the Buddhist Publication Society.

[Note: The printed edition

of this book includes two large fold-out pictorial supplements: "Tibetan

Wheel of Samsara" (after Waddell) and "Modern Wheel of Samsara" (by the

author). These are not reproduced in this electronic transcription. --

DharmaNet ed.]

This indeed has been said by the

exalted one:

Two knowable dhammas should be

thoroughly known -- mind and body; two knowable dhammas should be

relinquished -- unknowing and craving for existence; two knowable

dhammas should be realized -- wisdom and freedom; two knowable dhammas

should be developed -- calm and insight.

Eight are the bases of unknowing:

Non-comprehension in dukkha,

noncomprehension in dukkha's arising, non-comprehension in dukkha's

cessation, non-comprehension in the practice-path leading to dukkha's

cessation, non-comprehension in the past, non-comprehension in the

future, non-comprehension in past and future, non-comprehension in

Dependent Arising.

Eight are the bases of knowledge:

Comprehension in dukkha, comprehension

in dukkha's arising, comprehension in dukkha's cessation, comprehension

in the practice-path leading to dukkha's cessation, comprehension in the

past, comprehension in the future, comprehension in past and future,

comprehension in Dependent Arising.

Peace it is and Excellence it is, that

is to say -- the stilling of all conditions, the rejection of all

substrates (for rebirth), the destruction of craving, passionlessness,

cessation, Nibbana.

O Bhikkhus, there is that sphere where

is neither earth nor water nor fire nor air, nor the sphere of infinite

space; nor the sphere of infinite consciousness, nor the sphere of

no-thingness, nor the sphere of neither-perception-nor-non-perception;

not this world, nor another world, neither the moon nor the sun.

That I say, O bhikkhus, is indeed

neither coming nor going nor staying, nor passing-away and not arising.

Unsupported, unmoving, devoid of object -- that indeed is the end of

dukkha.

And this dhamma is profound, hard to

see, hard to awaken to, peaceful, excellent, beyond logic, subtle and to

be experienced by the wise.

-- Translated

from the Royal Chanting Book (Suan Mon Chabub Luang) compiled by H.H.,

the 9th Sangharaja of Siam, Sa Pussadevo, and printed at Mahamakut

Press, Bangkok).

Introduction

[^]

Upon the Full Moon of the month of

Visakha, now more than two thousand five hundred years ago, the religious

wanderer known as Gotama, formerly Prince Siddhattha and heir to the

throne of the Sakiyan peoples, by his full insight into the Truth called

Dhamma which is this mind and body, became the One Perfectly Enlightened

by himself.

His Enlightenment or Awakening, called

Sambodhi, abolished in himself unknowing and craving, destroyed greed,

aversion and delusion in his heart, so that "vision arose, super-knowledge

arose, wisdom arose, discovery arose, light arose -- a total penetration

into the mind and body, its origin, its cessation and the way to its

cessation which was at the same time complete understanding of the

"world," its origin, its cessation and the way to its cessation. He

penetrated to the Truth underlying all existence. In meditative

concentration throughout one night, but after years of striving, from

being a seeker, He became "the One-who-Knows, the One-who-Sees."

When He came to explain His great

discovery to others, He did so in various ways suited to the understanding

of those who listened and suited to help relieve the problems with which

they were burdened.

He knew with his Great Wisdom exactly what

these were even if his listeners were not aware of them, and out of His

Great Compassion taught Dhamma for those who wished to lay down their

burdens. The burdens which men, indeed all beings, carry round with them

are no different now from the Buddha-time. For then as now men were

burdened with unknowing and craving. They did not know of the Four Noble

Truths nor of Dependent Arising and they craved for fire and poison and

were then as now, consumed by fears. Lord Buddha, One attained to the

Secure has said:

"Profound, Ananda, is this Dependent

Arising, and it appears profound. It is through not understanding, not

penetrating this law that the world resembles a tangled skein of thread,

a woven nest of birds, a thicket of bamboos and reeds, that man does not

escape from (birth in) the lower realms of existence, from the states of

woe and perdition, and suffers from the round of rebirth."

The not-understanding of Dependent Arising

is the root of all sorrows experienced by all beings. It is also the most

important of the formulations of Lord Buddha's Enlightenment. For a

Buddhist it is therefore most necessary to see into the heart of this for

oneself. This is done not be reading about it nor by becoming expert in

scriptures, nor by speculations upon one's own and others' concepts but by

seeing Dependent Arising in one's own life and by coming to grips with it

through calm and insight in one's "own" mind and body.

"He who sees Dependent Arising, he sees

Dhamma."

Let us now see how this Teaching is

concerned with our own lives. The search of every living being is to find

happiness, in whatever state, human or non-human, they find themselves.

But what it is really important to know is this: the factors which give

rise to unhappiness, so that they can be avoided; and the factors from

which arise happiness, so that they can be cultivated. This is just

another way of stating the Four Noble Truths. In the first half of this

statement there is unhappiness or what is never satisfactory,

called in Pali language, Dukkha.

This Dukkha is the first Noble Truth which

we experience all the time, usually without noticing it, which does

not make the dukkha any less! First, there is occasional dukkha:

birth, old age, disease and death, for these events usually do not compose

the whole of life. Then we have frequent dukkha: being united with

what one dislikes, being separated from what one likes, not getting what

one wants, and this is everyday experience. Finally, as a summary of all

kinds of dukkha there is continuous dukkha: the five grasped-at

groups, that is to say body, feeling, perceptions, volitions (and other

mental activity) and consciousness, the components of a human being.

Explanation of these in full would take too long here but all the readers

are provided with these kinds of dukkha in themselves. They should look to

see whether these facts of existence are delightful or not. This Dhamma

"should be thoroughly known" in one's own person and life, that is where

the first Noble Truth may be discovered.

Then the factors which give rise to

unhappiness were mentioned. Here again one's person and life should be

investigated. Now when living creature are killed intentionally by me,

when I take what is not given, when I indulge in wrong conduct in sexual

relations, when I speak false words and when I take intoxicating drinks

and drugs producing carelessness -- now are these things factors for

happiness or unhappiness? When I covet the belongings of others, when I

allow ill-will to dwell in my heart, and when I have as the tenants of my

heart ignorance, delusion, and views which lead astray -- is this for my

welfare or destruction? There are many ways of describing these factors

which make for unhappiness but all of them derive from unknowing and

craving which are just two sides of the same thing. This is the Second

Noble Truth of the Arising of Dukkha. When craving is at work, when

unknowing clouds one's understanding, then one is sure to experience

dukkha. Lord Buddha instructs us for our own benefit and for the happiness

of others, that this craving "should be relinquished."

Now happiness in the second half of

the statement above can be of many kinds. Two kinds dependent upon

conditions can be seen illustrated by the world, while one kind,

unsupported by conditions "should be realized" in one's own heart. We are

all looking for happiness so let us see what is needed for it. First,

there is materially produced happiness. This is born of possessions and

jugglery with conditions of life "out there." Called amisa-sukha in

Pali, this happiness is most uncertain; for all the factors supporting it

are subject to instability and change. Moreover, they are out in the world

and not in one's own heart, so that they call for expert jugglery to save

one from dukkha. And failure and disappointment cannot be avoided if one

goes after this sort of happiness. So this sort of happiness is

short-lived and precarious. A great improvement on this is the happiness

which comes from practicing Dhamma, called non-material happiness or

niramisa-sukha. This kind of happiness is made sure whenever a person

performs wholesome kamma, such as doing the following ten things: giving,

moral conduct mind-development, reverence, helpfulness, dedicating

meritorious acts to others, rejoicing in the meritorious acts of others,

hearkening to Dhamma, teaching Dhamma and setting upright one's views.

People who practice this Dhamma, purifying their hearts in this way, are

sure to reap happiness. But this happiness, though more lasting than the

first, is not to be relied upon forever. As a fruit of it one may dwell

among the gods for aeons, or be born as a very fortunate man but even the

gods have to pass away, let alone man. And the fruits of kamma, good or

evil, are impermanent, so it cannot be relied upon to produce a permanent

happiness. This can only be found by removing entirely the cause for

dukkha: when craving is uprooted no growth of dukkha can take place. On

the contrary, with purity, compassion and wisdom one has reached the

Supreme Happiness of Nibbana which is stable, indestructible and never

subject to changing conditions. This is the Third Noble Truth of the

Cessation of Dukkha by the removal of its cause. A good deal of hard work

is needed to get to this "which should be realized," and that work must be

done along the right lines, hence the Fourth Noble Truth.

This is called the Truth of the Path,

"which should be cultivated." It comprises elements of wisdom: Right View

and Right Attitude; elements of moral conduct: Right Speech, Right Action,

and Right Livelihood; and elements of meditation: Right Effort, Right

Mindfulness and Right Collectedness. These will not be explained in detail

here.[1] It is certain that any one who

practices Moral Conduct, Collectedness and Wisdom in his life has the

conditions which sustain happiness. From his practice he may have

Dhamma-happiness or the Supreme Happiness, according to the degree he

practices, for the latter requires well-developed meditation both in calm

and in insight.

These Four Noble Truths -- Dukkha, Cause,

Cessation, and Path -- are the heart of the Dhamma and they are in the

heart of every man who cares to see them. From their seeing and

understanding comes happiness but by trying to escape them only more

misery is born.

These Truths are illustrated by the

formula of Dependent Arising which is found elaborated in various ways.

The simplest form is:

Craving being, dukkha is; by the arising

of craving, dukkha arises; craving not being, dukkha is not; by the

cessation of craving, dukkha ceases.

But Dependent Arising can be given in much

more detailed ways than this. The important principle to understand is

that whatever is experienced by us, all that arises due to many

conditions. An aspect which grows in size from birth throughout youth,

which develops certain characteristics in maturity, and as old age creeps

on becomes infirm in various ways, and finally dies. The processes which

govern this growth and decline are of great complexity and

interdependence. The body, to keep going at all, needs clothes, food,

shelter and medicines at least. But once the internal chemistry (also

dependently originated) starts the process leading to old age and death,

none of the exterior supporting conditions can do more than retard the

process for a little while. The body, as a whole, does not arise from

"no-cause" (the physical particles and kamma being its immediate causes);

nor is it derived from one cause. If examined, nothing which we

experience arises from only one, or no cause at all; on the contrary our

experiences all arises dependently. Sight is actually dependent on the eye

as base, the object to be seen, and the operation of eye-consciousness.

(There are other factors that also contribute: light, air,...) Similarly,

there is ear, sound, ear-consciousness; nose, smell, nose-consciousness;

tongue, taste, tongue-consciousness; body, touch, body-consciousness; and

mind, thoughts, mind-consciousness. All of our experience falls within

these eighteen elements and there is nothing which we know outside them.

It is also important to understand that

much of what one experiences arising dependently is the fruit of one's own

actions. The happiness one feels and the dukkha one feels, although

sometimes brought about by events in the physical world (landslides,

earthquakes, a sunny or a rainy day), is very often brought about by one's

own past intentional actions or kamma. And in the present time with each

deliberate action, one performs more kammas which will come to fruit as

experience in the future. So, if one wants to experience the fruits of

happiness, the seeds of happiness must be planted now. They may fruit

immediately, in this life, or in a future existence. We make ourselves, we

are the creators of ourselves, no one else has a hand in this creation.

And the Lord of Creation is no other than Ignorance or Unknowing. He is

the Creator of this Wheel of Samsara, of continued and infinitely varied

forms of dukkha. And this Lord resides in the hearts of all men who are

called "ordinary-men." We shall return to this in more detail later.

The History of the Wheel

[^]

Dependent Arising is explained many times

and in many different connections in the Discourses of Lord Buddha, but He

has not compared it to a wheel. This simile is found in the Visuddhimagga

("The Path of Purification") and in the other commentarial literature.

Although Theravada tradition has many references to this simile, it does

not seem to have been depicted at all. But in Northern India and

especially in Kashmir, the Sarvastivada school[2]

was strongly established and besides producing a vast literature upon

Discipline and the Further Dhamma (Vinaya and Abhidhamma), they produced

also a way of depicting a great many important Buddhist teachings by this

picture of the Wheel which is the subject of the present essay.

In Pali it is the bhava-cakka or

Samsara-cakka, which is variously rendered in English as the Wheel of

Life, the Wheel of Becoming or the Wheel of Rebirth.

In their collections of stories about Lord

Buddha and his disciples (known as Avadana), there is one which

opens with the story of this wheel. Readers will observe that the story

refers to Lord Buddha's lifetime and says that He has authorized the

painting of this picture, as well as laying down its contents. It is

certain that in the Buddha-time painting was well known (it is mentioned

several times in the Discourses and the Discipline) while the other facts

given in this short introductory story are quite in accord with the spirit

of the Pali Discourses. Even the collection of stories in which this

account is contained was compiled, according to some scholars, before the

Christian era. So if one does not believe that this painting was ordained

by Lord Buddha, still it has an age of two thousand years, a venerable

tradition indeed. Of all "teaching-aids" this expression of Buddhist

skillful-means (upaya-kosalla), must surely be the oldest. Now let

us turn to the story.

The Translation

[^]

"Lord Buddha was staying at Rajagaha,[3]

in the Bamboo Grove, at the Squirrels' Feeding-place. Now, it was the

practice of Venerable Mahamoggallana to frequent the hells for a certain

time, then the animal-kingdom, also to visit the ghosts, the gods and men.

Having seen all the sufferings to be found in the hells which beings there

experience as they arise and pass away, such as maiming, dismembering and

so forth; having witnessed how animals kill and devour others, how ghosts

are tormented by hunger and thirst, how the gods lose (their heavenly

state), fall (from it), are spoiled and come to their ruin, and how men

crave and come to naught but thwarted desires, -- having seen all this he

returned to Jambudipa (India) and reported this to the four assemblies.

Whatever (venerable one) had a fellow-bhikkhu or a bhikkhu-pupil leading

the holy life with dissatisfaction, he would take him to Venerable

Mahamoggallana (thinking): 'The Venerable Mahamoggallana will exhort and

teach him well'. And (truly) the Venerable Mahamoggallana would exhort and

teach him well. Such (dissatisfied bhikkhus) would again lead the holy

life with keen interest, even distinguishing themselves with the higher

attainments since they had been taught and exhorted so well by the

Venerable Mahamoggallana.

"At that time (when the Lord stayed at

Rajagaha), the Venerable Mahamoggallana was surrounded by the four

assemblies consisting of bhikkhus, bhikkhunis, pious laymen and women.

"Now the illustrious Enlightened Ones who

Know, (also) ask questions. Thus Lord Buddha asked the Venerable Ananda

(why the second of his foremost disciples was surrounded by the four

assemblies). Venerable Ananda then related Venerable Mahamoggallana's

experiences and said that he instructed discontented bhikkhus with

success.

"(The Lord replied:) 'The Elder Moggallana

or a bhikkhu like him cannot be at many places (at the same time for

teaching people). Therefore, in the (monastery) gateways a wheel having

five sections should be made.'

"Thus the Lord laid down that a wheel with

five sections should be made (whereupon it was remarked:) 'But the

bhikkhus do not know what sort of wheel should be made'.

"The Lord explained: 'The five bourns

should be represented -- the hellish bourn, that of the animal kingdom, of

ghosts, of men, and the bourn of the gods. In the lower portion (of the

wheel), the hells are to be shown, together, with the animal-kingdom and

the realm of the ghosts, while in the upper portion gods and men should be

represented. The four continents should also be depicted, namely,

Pubbavideha, Aparagoyana, Uttarakuru and Jambudipa.[4]

In the middle, greed, aversion and delusion must be shown, a dove

symbolizing greed,[5] a snake symbolizing

aversion, and a hog, delusion. Furthermore, the Buddhas are to be painted

(surrounded by their) halos pointing out (the way to) Nibbana. Ordinary

beings should be shown as by the contrivance of a water-wheel they sink

(to lower states) and rise up again. The space around the rim should be

filled with (scenes teaching) the twelve links of Dependent Arising in the

forward and reversed order. (The picture of the Wheel) must show clearly

that everything, all the time, is swallowed by impermanence and the

following two verses should be added as an inscription:

Make a start, leave behind (the

wandering-on)

firmly concentrate upon the Buddha's Teaching.

As He, Leader like an elephant, did

Nalagiri rout,

so should you rout and defeat the hosts of Death.

Whoever in this Dhamma-Vinaya will go

his way

ever vigilant and always striving hard,

Can make an end of dukkha here

and leave behind Samsara's wheel of birth and death.

"Thus, at the instance of the bhikkhus, it

was laid down by the Lord that the Wheel of Wandering-on (in birth and

death) with five sections should be made in the gateways (of monasteries).

"Now brahmans and householders would come

and ask: 'Reverend Sir, what is this painting about?'

"Bhikkhus would reply: 'We also do not

know!'

"Thereupon the Lord advised: 'A bhikkhu

should be appointed (to receive) visitors in the gateway and to show them

(the mural).'

"Bhikkhus were appointed without due

consideration (to be guest-receiver), foolish, erring, confused persons

without merit. (At this, it was objected:) 'They themselves do not know,

so how will they explain (the Wheel-picture) to visiting brahmans and

householders?'

"The Lord said: 'A competent bhikkhu

should be appointed.'"[6]

The Later History of the Tradition

[^]

Tibetan legend says that Lord Buddha

outlined the Wheel with grains of rice while walking with bhikkhus in a

rice field. However this may be, in India, at least in all the

Sarvastivada monasteries, this painting will have adorned the gateways,

arousing deep emotions in the hearts of those who knew its meaning, and

curiosity in others. It is a measure of how great was the destruction of

the Buddhist religion in India that not a single example survives

anywhere, since no gateways to temples are known to have survived. A

solitary painting in Ajanta cave number seventeen may perhaps be some form

of this wheel.

In the translation above, the pictures for

representing the twelve links of Dependent Arising were not given and it

is said that these were supplied from the scriptures by Nagarjuna, a great

Buddhist Teacher (some of whose verses are quoted below). From India the

pattern of this wheel was taken to Samye, the first Tibetan monastery, by

Bande Yeshe and there it was the Sarvastivada lineage of ordination which

was established. The tradition of painting this wheel thus passed to

Tibet, where, due to climatic conditions, it was painted in the vestibule

of the temple, there to strike the eyes of all who entered.

Tibetan tradition speaks of two kinds of

Wheel: the old-style and the new-style. The old-style is based upon the

text translated above, while the new-style introduces new features. The

great reformer, Je Tsongkhapa (b. 1357 C.E.), founder of the Gelugpa (the

Virtuous Ones, the school of which H.H. the Dalai Lama is the head), gave

authority for the division of the Wheel into six instead of five, and for

drawing the Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara in the guise of a Buddha in each of

the five non-human realms. Both these features may be seen upon the

drawing of the Tibetan-style Wheel. The sixth realm is that of the titans

(asura) who war against the gods of the sensual-sphere heavens. These

troublesome and demonic characters are included in a separate part of the

world of the gods in my drawing. The introduction of a Buddha-figure into

each realm illustrates the universal quality of a Buddha's great

compassion, for Avalokitesvara it the embodiment of enlightened

compassion. The writer has preferred to retain the old-style

representation according to the text as it agrees perfectly with Theravada

teachings.

The terrors and violence of samsara, which

are with us all the time, may be seen plainly in the ravishment of Tibet

by the Chinese invaders. Tibetan artists have kept this tradition alive to

the present day and still paint under difficulties as refugees in India.

But this ancient way of presenting Dhamma deserves to be more widely known

and appreciated. Buddhist shrines could well be equipped with

representations of it in the present day, to remind devotees of the nature

of this whirling wheel of birth and death.

The Symbolism and its Practical Meaning

[^]

The Hub

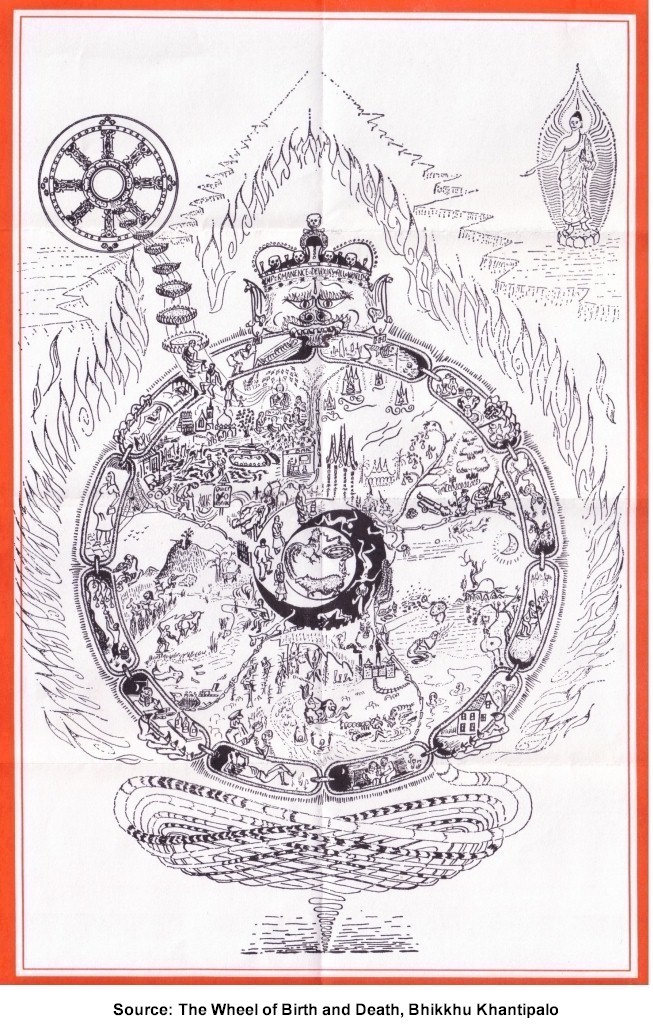

We now turn to the pictures of the

Bhava-cakka accompanying this book. One is from a Tibetan original after

Waddell. The second is a modern version executed by the author, in which

the scenes and figures have been given a contemporary coloring.

The hub of this painting is the central

point for us who live in the realm of samsara, so it is the best point to

start a description of the symbolism. In this center circle, a cock, a

snake and a hog wheel around, each having in its mouth the tail of the

animal in front. These three, representing Greed, Aversion and Delusion

which are the three roots of all evil, are depicted in the center because

they are the root causes for experience in the wandering on. When they are

present in our hearts then we live afflicted in the transitory world of

birth and death but when they are not there, having been destroyed by

wisdom or pañña, developed in Dhamma-practice, then we find rest, the

unshakable peace of Nibbana. It is notable that Tibetan paintings show

these creatures against a blue ground, showing that even these afflictions

of mind, although powerful, have no real substance and are void, as are

all the other elements of our experience.

The cock of fiery yellow-red represents

greed (lobha). This greed includes every desire for all kinds of "I

wish, I want, I must have, I will have" and extends from the violent

passion for gross physical form, through attachments to views and ideas,

all the way to the subtle clinging to spiritual pleasures experienced by

meditators. The color of the cock, a fiery red, is symbolic of the fact

that the passions burn those who indulge in them. Passions and desires are

hot and restless, just like tongues of flame, and never allow the heart to

experience the cool peace of non-attachment. The cock is chosen as a

symbol of greed because as an animal it is observed to be full of lust and

vanity.

In the cock's beak there is the tail of a

green snake indicating that people who are not able to "satisfy" their

ocean-like greeds and lusts tend to become angry. Aversion (dosa)

of any form springs up when we do not get what we want, or when we get

what we do not want. This also can be very subtle, from aversion to mental

states ranging through hostile thoughts against other beings, to

expressions of inward resentment finding their way out in untruthful,

malicious or angry words, or as physical violence. The greenness of the

snake indicates the coldness, the lack of sympathy with others, while the

snake itself is an animal killing other beings by poison and

strangulation, which is exactly what aversion does to those who let it

grow in their hearts. Our lives can be corrupted by this venomous beast

unless we take very good care to remove it.

At the bottom of the picture there is a

heavy hog, the tail of which is chewed by aversion's snake, while in turn

it champs upon the tail feathers of greed's cock. This heavy hog is black

in color and represents delusion (moha). This black hog, like its

brethren everywhere, likes to sleep for long, to root for food in filth

and generally to take no care at all over cleanliness. It is a good symbol

for delusion which prevents one from understanding what is advantageous

and what is deleterious to oneself. Its heaviness is that sluggishness of

mind and body which it induces in people, called variously stupidity,

dullness, boredom; but worry and distraction with skeptical doubt also

arise from this delusion-root. One who is overwhelmed by delusion does not

know why he should restrain himself from evil, for he can see neither his

own benefit with wisdom, nor the benefit of others by compassion -- all is

blanketed by delusion. He does not know, or does not believe that kamma

(intentional actions) have results according to kind. Or he has wrong

views which lead him astray from the highway of Dhamma. When people do not

get what they want either using greed or aversion, then they turn dull and

the pain of their desire is dulled by delusion. From this black hog are

born the fiery cock and the cold green snake.

These three beasts, none more dangerous

anywhere, are shown each biting the tail of the other, meaning that really

they are inseparable, so that one cannot have, say, greed, without the

other monsters lurking in its train. Even characters which are rooted

predominantly in one of these three, have the other two present, while

most people called "normal" have a sort of unhealthy balance of these

three in their hearts, ever ready to influence their actions when a

suitable situation occurs. These three beasts revolve endlessly in the

heart of the ordinary-man (puthujjana) and ensure that he

experiences plenty of dukkha. One should know for one-self whether these

beasts control one's own heart, or not.

The First Ring

Out from the innermost circle, the first

ring is divided into two (not shown at all upon the Tibetan version

illustrated here), one half with a white background and the other having a

black background. In the former, four people are seen ascending: the

bhikkhu holding a Dhamma-light goes on in front, being followed by a

white-robed nun (upasika), after which come a man and a woman in

present day dress. The four of them represent the Buddhist Community made

up of monks, nuns, laymen and laywomen. They are representative of anyone

practicing the path of good conduct in mind, speech and body. They

represent as well two classes of persons: "going from dark to light" and

"going from light to light." In the first case, they are born in poor

circumstances and have few opportunities due to past evil kamma but in

spite of this, they make every effort to practice Dhamma for their own

good and others' happiness. Thus they go towards the light, for the fruit

of their present kamma will be pleasant and enjoyable. The latter class,

"going from light to light," are those people who have attained many

benefits with plentiful opportunities in their present life, due to having

done much good kamma in the past. In the present they continue with their

upward course devoting themselves to further practice of Dhamma in their

lives.

What is this Dhamma-practice? There are

two lists both of ten factors which could be explained here but the space

required would be too great for more than a summary. The first list is

called the ten Skilled Kamma-paths,[7] three of

which pertain to bodily action, four to speech and three to mental action.

"Paths" here means "ways of action" and "skillful" means "neither for the

deterioration of one's own mind nor for the harm of others." The bodily

actions which one refrains from are: destroying living creatures, taking

what is not given, and wrong conduct in sexual desires. In speech, the

four actions which should be avoided are: false speech, slanderous speech,

harsh speech and foolish chatter. The three actions of mind which should

be avoided are: covetousness, ill-will, and wrong views. Anyone who

restrains himself from these ten, practices a skillful path, a white path

which accords with the first steps of training in Dhamma.

The other ten factors are called the Ten

Ways of making Puñña[8] (meaning actions

purifying the heart). They have a different range from the first list of

ten, being divided into three basic ways and seven secondary ones. The

basic factors are giving (dana), moral conduct (sila), and

mind development (bhavana), while the remaining seven are counted

as aspects of these three: reverence, helpfulness, dedicating one's puñña

to others, rejoicing in other's puñña, listening to Dhamma, teaching

Dhamma, and straightening out one's views. These actions lead to

uprightness, skillful conduct and to the growth in Dhamma of oneself, as

well as the benefit of others.

Those who tread upon this white path going

toward the light are able to be born in two bourns: either as men, or as

"shining-ones" -- the gods in the three sorts of heavens of sensuality,

subtle form, and formlessness. A life of good practice is thus usually

followed by a life in one of these two bourns, called sugati or the

good bourns. But Lord Buddha does not declare that everyone who has

led such a life is necessarily born there. This depends not only upon the

intensity of their Dhamma-practice but also upon the vision which

arises at the time of death. Through negligence at the last moment, one

can slip into the three evil bourns difficult to get out of. The round of

Samsara is very dangerous, even for those who lead almost blameless lives.

More of this below. To be born in the two good bourns is the fruiting of

puñña or skillful kamma and the more purified one's heart, the higher and

more pleasant will be one's environment.

In the dark half of the ring, naked beings

are tumbling downwards in disorder. Their nakedness symbolizes lack of

shame in doing evil and their disorder shows the characteristic of evil to

cause disintegration and confusion. "Downwards" means that they are

falling, by the commission of sub-human actions, to sub-human states of

existence. In some Tibetan versions they are chained together and pulled

downwards by a female demon who squats at the bottom. This demoness is

craving of tanha (a noun of female gender). This craving is, of course,

not outside those who follow the path of evil but in their own hearts. On

this path there are two sorts of persons, those "going, from light to

dark" and those "going from dark to dark." The former have good

opportunities in this life but do not make use of them, or else use them

for evil ends without laying up any further store. Instead, they prefer

from delusion to store up evil now for fear and distress in future. Those

who go from dark to dark do not have even the advantages of the former

group for they are born in conditions of deprivation due to past evil

kamma and then, driven on by the fruit of suffering received by them, they

commit more evil.

The Ten Unskillful Kamma-paths are the

ways along which they walk: destroying living creatures, taking what is

not given, wrong conduct in sexual desires; false speech, slanderous

speech, harsh speech, foolish chatter; covetousness, ill-will and

wrong-views. They do not delight in making puñña but are by nature, mean,

immoral, undeveloped in mind, proud, selfish, grasp at possessions,

envious, never listen to Dhamma and certainly never teach it, while their

hearts are ridden with confused and contradictory views and ideas.

For their pains, having pursued evil,

these beings upon their death, already having destroyed "humanness" in

themselves, fall down to the three lower states which are called the Evil

Bourns (duggati). These are, in order of deterioration and increase

of suffering: the hungry ghosts, the animals, and the hell-wraiths. Truly

a case of:

do good, good fruit

do bad, bad fruit

as the Thai proverb says. These two

half-circles are also an illustration of the refrain which closes every

one of the Avadana stories: "Thus bhikkhus, completely black kamma bears

completely evil effects; completely white kamma bears completely good

effects; and composite kamma bears composite effects. Therefore, bhikkhus,

abstain from doing completely black kamma and composite kamma; strive to

do kamma completely white. Thus, O bhikkhus, must you train yourselves."

The Five Divisions

The two good bourns and the three evil

bourns contain the whole range of possibilities for rebirth. In most

Tibetan illustrations, including the one shown here, a sixth bourn is

given, by dividing the devas and asuras (the gods and anti-gods or

titans). In this section the five, or six bourns will be described,

together with the ways to get to them. Birth in any bourn is a fruit or

effect and here we shall see the causes.

A person who has done evil persistently,

or even one heavy crime, is likely to see at the time of death a vision,

either relating to his past evil actions, or else to the bourn which his

past evil actions or kamma have prepared for him. When his physical body

is no longer a suitable basis to support life, his mind creates a body

ghostly and subtle in substance, which then and there begins to experience

one of the evil bourns. But in case his kamma drives him to be born as

animals, there is the vision of animals copulating and he is dragged into

the womb or egg of those animals.

Kamma which leads to birth as an animal is

a strong interest in the things which mankind shares with the animals,

that is, eating, drinking and sex. If a man strengthens the animal in

himself, to become an "animal-man," he can expect only to be born as an

animal. Human beings interested in only these things, strengthening the

Evil Root of Delusion in their minds, have already the minds of animals.

There is no essential "man-ness" which can prevent such a catastrophe, for

no unchanging human soul exists. If a man wishes to guard himself against

this, he must protect the conditions for humanity (manussa-dhamma)

which are the Five Precepts. Sinking below the level of conduct of these

precepts, is to sink into the sub-human levels. Once rebirth as an animal

has taken place it is by no means easy to gain human birth again, as

Venerable Nagarjuna has written:

More difficult is it to rise

from birth as animal to man,

Than for the turtle blind to see

the yoke upon the ocean drift;

Therefore, do you being a man

practice Dhamma and gain its fruits.

-- L.K. 59 ("The

Letter of Kindheartedness" by Acarya Nagarjuna, in "Wisdom Gone Beyond",

Social Service Association Press of Thailand, Phya Thai Road, Bangkok,

Siam.)

Kamma dragging one to the hells, which are

the most fearful and miserable states, are actions involving hatred,

killing, torture and violence generally. People lead themselves to

experience hell because they have made the Evil Root of Aversion very

strong within themselves.

On the other hand, those who have

strengthened the Evil Root of Greed while they were men, having been mean,

possessive and selfish, are liable to arise as spirits with strong

cravings forever unsatisfied, for which reason they are known as "hungry"

ghosts.

However, it does sometimes happen that one

who has led an evil life turns sincerely to religion upon his deathbed.

When this occurs, with his mind centered upon Dhamma and purified by

faith, a person like this may be reborn among men, even arise among the

devas. That evil kamma which has been done though it may have no chance to

fructify in those good bourns, remains a potential for creating very

unpleasant results whenever conditions are favorable to its fruition. The

reverse of this may happen, as when good and noble men become distracted

at death and so remember some small evil done, or see a vision of evil

done in some past life, the result of which is the arising of unwholesome

consciousness leading to the evil bourns.

It is more usual for one who has followed

the path of white deeds to be born as a man or among the gods. The basis

for the former is the practice of the Five Precepts which constitute the

level of humanness. They are in brief: refraining from destroying living

creatures; refraining from taking what is not given; refraining from wrong

conduct in sexual desires; refraining from false speech, and refraining

from distilled and fermented intoxicants which cause carelessness. Those

who refrain from such things, having really lived as men, having

strengthened the base of humanness in their own hearts, are born again as

men well-endowed with the riches of fine qualities; of varied

opportunities, as well as with a wealth of worldly goods.

The path to the heavens is cultivated by

those who make special efforts to live with purity and self-restraint,

exercising loving-kindness toward all beings and so purifying their minds

to some extent through meditation. At the time of death, having fulfilled

the ten Skillful Kamma paths and the ten Ways of Making Puñña, the heart

will be joyful and peaceful to varying degrees, which will result in the

experience of arising in one of the many heavenly levels according to the

degree of purity and concentration which has been attained.

All these possibilities are within the

scope of the mind, the quality of which can be changed in this way or that

by kamma, good or bad. From the type of mind which performs the duty of

relinking-consciousness at birth, is determined the kind of sense-organs

possessed by a being, and hence the kind of world experienced by him.

Perception varies -- as the famous Buddhist verse puts it:

As a water-vessel is

variously perceived by beings:

Nectar to celestials,

is for a man plain drinking-water,

While to the hungry ghost it seems

a putrid ooze of pus and blood,

Is for the water serpent-spirits

and the fish a place to live in,

While it is space to gods who dwell

in the sphere of infinite space.

So any object, live or dead,

within the person or without --

Differently is seen by beings

according to their fruits of kamma.

From such verses we catch a glimpse of the

mysterious depths of the mind, and of the truth of the Exalted Buddha's

words which open the Dhammapada:

Before all dhammas goes the mind; Mind

is the chief, mind-made are they...

To come now to a description of the

picture. In the world of the gods or "shining-ones" (deva, upper

right, but topmost in the Tibetan version), the gilded palaces and

glittering jewel trees of the gods of sensuality are shown in the lower

part of the drawing. The Tibetan picture shows more details of these

superlatively beautiful worlds in which there is also a kind of subtle

sexual relationship. Being based upon sensuality, as this world of men is,

these devas must also pay the price for this -- which is conflict. This

conflict is an ever-recurring battle with the asuras, the anti-gods or

titans who have in past times fallen through their quarrelsome nature from

the heavens and who now enviously try to invade the celestial realms. In

my picture, they share a segment of the world of gods and they are

equipped with ancient and modern weapons and are in the dress of soldiers.

But they do not only battle with the gods but also among themselves and so

a bit of insubordination is depicted as well. The Tibetan picture gives

them a world to themselves among the frontiers of which they are fleeing

from the victorious heavenly hosts led upon a very large elephant by

Sakka, the lord of the sensual-realm gods. These titans only understand

force, so the Buddha shown in their world bears a sword with which to duly

impress them, after which they may be able to hear a little Dhamma. By

contrast, the Buddha appearing among the gods bears a lute, in order to

lure them into listening to Dhamma sung in exquisite strains, for it was

believed that they would not be interested in mere spoken words!

Above the battling of the sensual-realm

gods dwell the Brahmas of subtle form and of formlessness, experiencing

meditative happiness, serene joy, or sublime equanimity. The Tibetan

picture also shows a magnificent Brahma world palace in the upper lefthand

corner. About all this heavenly splendor, Ven. Nagarjuna warns us:

"Great King, although celestial worlds

have pleasures great to be enjoyed,

Greater the pain of dying there.

From often contemplating this

a noble person does not wish

For transient heavenly joys."

-- L.K. 98

He goes on to speak of the devas as those

"Who, dying from celestial realms

with no remaining merit fruits

Must take up their abode

according to the karma past, --

With birth as beast or hungry ghost,

or else arise in hell."

-- L.K. 101

The Brahmas of formlessness dwelling for

unthinkable ages in the realms of infinite space, infinite consciousness,

no-thingness, and neither-perception-nor-non-perception being quite

without any form, naturally cannot be shown, but even their states are not

eternal, but come to an end.

Among men (upper left in both

pictures), the progress of the human-being is shown: birth (a

perambulator; old-age, sickness (hospital sign) and death (a bloated

corpse in a graveyard), but with this basis of dukkha, men can also

understand Dhamma. Lord Buddha, foremost among men, sits highest in the

human world teaching Dhamma in a forest grove to his first five disciples.

In the original version which my picture follows, He is shown only in the

human world, thus emphasizing the value of human birth, during which it is

possible to gain insight into Dhamma. The religious aspirations of man are

represented by a Hindu temple, a Christian church and Muslim mosque, while

a war and a bar show his tendencies towards aversion and greed. The

Tibetan picture shows several mundane activities such as plowing the

fields, while people climb towards the top of the picture where there is a

temple in which they can listen to Dhamma. In the center stands a Buddha

carrying the almsbowl and staff, showing to men the way of peacefulness

leading to Sublime Peace of Nibbana. This is shown in my picture by the

sure Dhamma-path which issues from the mouth of the Exalted Buddha. Upon

this way a bhikkhu lends a hand to help householders out of the realms of

samsara, leading them forward upon the Eightfold Path. Venerable Nagarjuna

has this to say:

"Who though he has been born a man

yet gives himself to evil ways,

More foolish is he than the fool

who fills with vomit, urine, dung

Golden vessels jewel-adorned --

harder man's birth to gain than these."

-- L.K. 60

Hungry ghosts or peta (lower right

in my picture, lower left in the Tibetan) crave for food and drink but

find that it turns to fire or foul things when they are able to get it. I

have shown a huge moon and a tiny sun, as the verse says:

"From want of merit, hungry ghosts

in summer find the moon is hot,

in winter sun is cold;

Barren are the trees they see

and mighty rivers running on

dry up whene'er they look at them."

-- L.K. 95

Then there is a sky-going peta being torn

to shreds by birds, as seen by Venerable Moggallana; one "resting" upon

rocks under a leafless tree which is the simile used by the Exalted Buddha

in the suttas to symbolize the sole comforts of this realm, and two ghosts

sunk in the water up to their lower lips, their gaping mouths just a

little too high to get any of it. The state of Tantalus was obviously

birth among the hungry ghosts! The ghosts all have bloated bellies,

extremely slender necks and "needle-mouths." Their sufferings are

illustrated further in the Tibetan. They have to bear intense cravings for

food and drink and then more sufferings when they manage to get a little

of it, for it turns to swords and knives in their bellies. The Buddha in

this "abundantly painful" realm carries celestial food to allay the

ghosts' cravings. In the words of Ven. Nagarjuna:

"Lord Buddha has declared the cause

why beings come to birth as ghosts,

torments to endure

For when as men they gave no gifts,

or giving gave with avarice --

They ghostly kamma made."

-- L.K. 97

The animals, in the Tibetan

illustration, are being encouraged in the Dhamma by a Buddha holding a

book, illustrating the point that animals have little ability to

understand and are in need of wisdom. My picture illustrates the

sufferings of animal-life as described by Ven. Nagarjuna:

"Then should you come to birth as beast

many are the pains --

Killing, disease and gory strife

binding, striking too.

Void of peaceful, skillful acts

beasts slay and kill without remorse.

Some among beasts are slain because

they produce pearls, or wool, or bones,

or valued are for meat or hide.

Others are pressed to do men's work

by blows or sticks or iron hook,

by whipping them to work."

-- L.K. 89-90

In the animal-world where feelings

experienced are "painful, sharp and severe," one can see the dukkha, the

hunter and the hunted, in my illustration. The birds of the air are being

shot while a vulture is feeding on its prey. A wasp struggling in the net

of a spider represents the horrors of life among the insects, while among

the larger animals, a buffalo is being forced to work, a deer is being

shot and a lion feeds upon his prey. The fish fare no better and are shown

being devoured by larger fish, or else hooked and netted by men.

Slithering down the division of this world from the hells, there is a

gecko. The Tibetan picture illustrates the diversity of animal life and

shows, under the waters, the palace of the serpent-spirits or naga, half

snake and half man.

The hells, which are not permanent

states of course, have some new horrors of our day: for railway lines run

into a concentration camp from the chimneys of which belches sinister

black smoke, while a uniformed member of some secret police force compels

a suppliant hell-wraith to swallow molten metal. Towards the viewer flows

the river of caustic soda called Vaitarani which burns the flesh off the

bones of those swirling along in it, mingled with a stream of blood from

the clashing mountains. Whatever torments hell-wraiths experience, though

their bodies are mangled, crushed and ripped apart, yet they survive still

for vast ages of time experiencing feelings which are "exclusively

painful, sharp and severe," unrelenting and uninterrupted:

"As highest is the bliss that comes

from all desires' cessation --

No higher bliss than this!

So worst the woe that's known in hell

Avici with no interval --

No woe is worse than this!"

-- L.K. 85

In the foreground is the hell of filth

where hell-wraiths, who as men had corrupted the innocent, are devoured by

gigantic maggots while floundering in a stinking ooze. To the left are the

trees of the sword-blade forest which have to be climbed so that hell

wraiths are pierced through and through. This particular aspect of hell is

said to be the punishment which adulterers bring on themselves. Various

murderers and torturers are impaled upon stakes while a steel-beaked bird

rips out the entrails of former cock-fighters. Venerable Nagarjuna has

some more verses upon these lower and most-miserable states:

"The criminal who has to bear

throughout a single day

The piercing of three hundred spears

as punishment for crime,

His pain can nowise be compared

to the least pain found in hell.

The pains of hell may still persist

a hundred crores of years --

Without respite, unbearable

So long the fruits of evil acts

do not exhaust the force --

So long continues life in hell."

-- L.K. 86-87

Jetsun Milarepa, the great sage and poet

of Tibet, who had seen the heavens and hells and other states, once sung

this verse:

"Fiends filled with cravings for

pleasures

Murder even their parents and teachers,

Rob the Three Gems of their treasures,

Revile and falsely accuse the Precious Ones,

And condemn the Dhamma as untrue:

In the hell of unceasing torment

These evil-doers will be burned..."[9]

Those who now violate the peoples of Tibet

and their Dhamma might well take note! This brief survey of the Five

Bourns (pañcagati) may be concluded with a verse of exhortation

from "The Letter of Kindheartedness":

"If your head or dress caught fire

in haste you would extinguish it,

Do likewise with desire --

which whirls the wheel or wandering-on

And is the root of suffering,

No better thing to do!"

-- L.K. 104

The Rim of the Wheel (Dependent Arising)

[^]

The Twelve-linked Chain

Our description has now come to the Rim,

or felly of the Wheel, which depicts the Twelve Links of Dependent

Arising. It is these links which chain the entire universe of beings to

re-becoming and to suffering.

It is a well-established tradition to

explain this chain as referring to three lives (past, present and future).

While the present is the only time which is real, it has been moulded in

the past. It is in the present that we produce kamma of mind, speech and

body, to bear fruit in the future. In the twelve nidanas or "links" around

this wheel are set out the whole pattern of life and in it all questions

relating to existence are answered. The teaching of Dependent Arising,

central in our Dhamma-Vinaya, is not, however, for speculation but should

be investigated and seen in one's own and others' lives, and finally it

may be perceived in one's own heart where all the Truths of Dhamma become

clear after practice. But people who do not practice Dhamma are called

"upholders of the world"; they let this wheel whirl them round from

unknowing to old-age and death. The Exalted Buddha urged us not to be

"world upholders" but through Dhamma-practice to relinquish greed,

aversion and delusion so that by the cessation of unknowing there comes to

be a cessation of birth, old-age and death.

Now let us have a look at these twelve

links in brief.

First Link:

Unknowing (avijja)

This Pali word "avijja" is a negative term

meaning "not knowing completely" but it does not mean "knowing nothing at

all." This kind of unknowing is very special and not concerned with

ordinary ways or subjects of knowledge, for here what one does not know

are the Four Noble Truths, one does not see them clearly in one's own

heart and one's own life. In past lives, we did not care to see dukkha

(1), so we could not destroy the cause of dukkha (2) or craving

which has impelled us to seek more and more lives, more and more

pleasures. The cessation of dukkha (3) which perhaps could have

been seen by us in past lives, was not realized, so we come to the present

existence inevitably burdened with dukkha. And in the past we can hardly

assume that we set our feet upon the practice-path leading to the

cessation of dukkha (4) and we did not even discover Stream-entry. We

are now paying for our own negligence in the past.

And this unknowing is not some kind of

first cause in the past, for it dwells in our hearts now. But due to this

unknowing, as we shall see, we have set in motion this wheel bringing

round old age and death and all other sorts of dukkha. Those past "selves"

in previous lives who are in the stream of my individual continuity did

not check their craving and so could not cut at the root of unknowing. On

the contrary they made kamma, some of the fruits of which in this present

life I, as their causal resultant, am receiving.

The picture helps us to understand this: a

blind old woman (avijja is of feminine gender) with a stick picks her way

through a petrified forest strewn with bones. It is said that the original

picture here should be an old blind she-camel led by a driver, the beast

being one accustomed to long and weary journeys across inhospitable

country, while its driver could be craving. Whichever simile is used, the

beginninglessness and the darkness of unknowing are well suggested. We are

the blind ones who have staggered from the past into the present -- to

what sort of future?

Depending on the existence of unknowing in

the heart there was volitional action, kamma or abhisankhara, made in

those past lives.

Second Link:

Volitions (sankhara)

Intentional actions have the latent power

within them to bear fruit in the future -- either in a later part of the

life in which they were performed, in the following life, or in some more

distant life, but their potency is not lost with even the passing of

aeons; and whenever the necessary conditions obtain that past kamma may

bear fruit. Now, in past lives we have made kamma, and due to our

ignorance of the Four Noble Truths we have been "world-upholders" and so

making good and evil kamma we have ensured the continued experience of

this world.

Beings like this, obstructed by unknowing

in their hearts have been compared to a potter making pots: he makes

successful and beautiful pottery (skillful kamma) and he is sometimes

careless and his pots crack and break up from various flaws (unskillful

kamma). And he gets his clay fairly well smeared over himself just as

purity of heart is obscured by the mud of kamma. The simile of the potter

is particularly apt because the word Sankhara means "forming,"

"shaping," and "compounding," and therefore it has often been rendered in

English as "Formations."

Depending on the existence of these

volitions produced in past lives, there arises the consciousness called

"relinking" which becomes the basis of this present life.

Third Link:

Consciousness (viññana)

This relinking consciousness may be of

different qualities, according to the kamma upon which it depends. In the

case of all those who read this, the consciousness "leaping" into a new

birth at the time of conception, was a human relinking consciousness

arising as a result of having practiced at least the Five Precepts, the

basis of "humanness" in past lives. One should note that this relinking

consciousness is a resultant, not something which can be controlled by

will. If one has not made kamma suitable for becoming a human being, one

cannot will, when the time of death comes round, "Now I shall become a man

again!" The time for intentional action was when one had the opportunity

to practice Dhamma. Although our relinking-consciousness in this birth is

now behind us, it is now that we can practice Dhamma and make more sure of

a favorable relinking consciousness in future -- that is, if we wish to go

on living in Samsara.

This relinking-consciousness is the third

constituent necessary for conception, for even though it is the mother's

period and sperm is deposited in the womb, if there is no "being" desiring

to take rebirth at that place and time there will be no fertilization of

the ovum.

Appropriately, the picture shows a monkey,

the consciousness leaping from one tree, the old life, to another tree.

The old tree has died, while the one towards which it jumps is laden with

fruits -- they may be the fruits of good or evil. The Tibetan picture

shows a monkey devouring fruit, experiencing the fruits of deeds done in

the past.

Dependent upon relinking-consciousness

there is the arising of mind-body.

Fourth Link:

Mind-body (Nama-rupa)

This is not a very accurate translation

but gives the general meaning. There is more included in rupa that is

usually thought of as body, while mind is a compound of feeling,

perception, volition and consciousness. This mind and body is two

interactive continuities in which there is nothing stable. Although in

conventional speech we talk of "my mind" and "my body," implying that

there is some sort of owner lurking in the background, the wise understand

that laws govern the workings of both mental states and physical changes

and mind cannot be ordered to be free of defilements, nor body told that

it must not grow old, become sick and die.

But it is in the mind that a change can be

wrought instead of drifting through life at the mercy of the inherent

instability of mind and body. So in the illustration, mind is doing the

work of punting the boat of psycho-physical states on the river of

cravings, while body is the passive passenger. The Tibetan picture shows a

coracle being rowed over swirling waters with three (? or four) other

passengers, who doubtless represent the other groups or aggregates

(khandha).

With the coming into existence of

mind-body, there is the arising of the six sense-spheres.

Fifth Link:

Six sense-spheres (salayatana)

A house with six windows is the usual

symbol for this link (but the Tibetan shows a house with one (?) window).

These six senses are eye, ear, nose, tongue, touch and mind, and these are

the bases for the reception of the various sorts of information which each

can gather in the presence of the correct conditions. This information

falls under six headings corresponding to the six spheres: sights, sounds,

smells, tastes, tangibles and thoughts. Beyond these six spheres of sense

and their corresponding six objective spheres, we know nothing. All our

experience is limited by the senses and their objects with the mind

counted as the sixth. The five outer senses collect data only in the

present but mind, the sixth, where this information is collected and

processed, ranges through the three times adding memories from the past

and hopes and fears for the future, as well as thoughts of various kinds

relating to the present. It may also add information about the spheres of

existence which are beyond the range of the five outer senses, such as the

various heavens, the ghosts and the hell-states. A mind developed through

collectedness (samadhi) is able to perceive these worlds and their

inhabitants.

The six sense-spheres existing, there is

contact.

Sixth Link:

Contact (phassa)

This means the contact between the six

senses and the respective objects. For instance, when the necessary

conditions are all fulfilled, there being an eye, a sight-object, light

and the eye being functional and the person awake and turned toward the

object, there is likely to be eye-contact, the striking of the object upon

the sensitive eye-base. The same is true for each of the senses and their

type of contact. The traditional symbol for this link shows a man and a

woman embracing.

Where contact arises, feeling exists.

Seventh Link:

Feeling (vedana)

When there have been various sorts of

contact through the six senses, feelings arise which are the emotional

response to those contacts. Feelings are of three sorts: pleasant, painful

and neither pleasant nor painful. The first are welcome and are the basis

for happiness, the second are unwelcome and are the basis for dukkha while

the third are the neutral sort of feelings which we experience so often

but hardly notice.

But all feelings are unstable and liable

to change, for no mental state can continue in equilibrium. Even moments

of the highest happiness whatever we consider this is, pass away and give

place to different ones. So even happiness which is impermanent based on

pleasant feelings is really dukkha, for how can the true unchanging

happiness be found in the unstable? Thus the picture shows a man with his

eyes pierced by arrows, a strong enough illustration of this.

When feelings arise, cravings are

(usually) produced.

Eighth Link

Craving (tanha)

Up to this point, the succession of events

has been determined by past kamma. Craving, however, leads to the making

of new kamma in the present and it is possible now, and only now, to

practice Dhamma. What is needed here is mindfulness (sati), for without it

no Dhamma at all can be practiced while one will be swept away by the

force of past habits and let craving and unknowing increase themselves

within one's heart. When one does have mindfulness one may and can know

"this is pleasant feeling," "this is unpleasant feeling," "this is neither

pleasant nor unpleasant feeling" -- and such contemplation of feelings

leads one to understand and beware of greed, aversion and delusion, which

are respectively associated with the three feelings. With this knowledge

one can break out of the Wheel of Birth and Death. But without this

Dhamma-practice it is certain that feelings will lead on to more cravings

and whirl one around this wheel full of dukkha. As Venerable Nagarjuna has

said:

"Desires have only surface sweetness,

hardness within and bitterness --

deceptive as the kimpa-fruit.

Thus says the King of Conquerors.

Such links renounce -- they bind the world

Within samsara's prison grid.

If your head or dress caught fire

in haste you would extinguish it,

Do likewise with desire --

Which whirls the wheel of wandering-on

and is the root of suffering.

No better thing to do!"

-- L.K. 23, 104

In Sanskrit, the word trisna (tanha) means

thirst, and by extension implies "thirst for experience." For this reason,

craving is shown as a toper guzzling intoxicants and in my picture I have

added three bottles -- craving for sensual sphere existence and the

craving for the higher heavens of the Brahma-worlds which are either of

subtle form, or formless.

Where the kamma of further craving is

produced there arises Grasping.

Ninth Link:

Grasping (upadana)

This is an intensification and

diversification of craving which is directed to four ends: sensual

pleasures, views which lead astray from Dhamma, external religious rites

and vows, and attachment to the view of soul or self as being permanent.

When these become strong in people they cannot even become interested in

Dhamma, for their efforts are directed away from Dhamma and towards

dukkha. The common reaction is to redouble efforts to find peace and

happiness among the objects which are grasped at. Hence both pictures show

a man reaching up to pick more fruit although his basket is full already.

Where this grasping is found there

Becoming is to be seen.

Tenth Link:

Becoming (bhava)

With hearts boiling with craving and

grasping, people ensure for themselves more and more of various sorts of

life, and pile up the fuel upon the fire of dukkha. The ordinary person,

not knowing about dukkha, wants to stoke up the blaze, but the Buddhist

way of doing things is to let the fires go out for want of fuel by

stopping the process of craving and grasping and thus cutting off

Unknowing at its root. If we want to stay in samsara we must be diligent

and see that our becoming, which is happening all the time shaped

by our kamma, is becoming in the right direction. This means

becoming in the direction of purity and following the white path of

Dhamma-practice. This will contribute to whatever we become, or do not

become, at the end of this life when the pathways to the various realms

stand open and we become according to our practice and to our

death-consciousness.

Appropriately, Becoming is

illustrated by a pregnant woman.

In the presence of Becoming there is

arising in a new birth.

Eleventh Link:

Birth (jati)

Birth, as one might expect, is shown as a

mother in the process of childbirth, a painful business and a reminder of

how dukkha cannot be avoided in any life. Whatever the future life is to

be, if we are not able to bring the wheel to a stop in this life,

certainly that future will arise conditioned by the kamma made in this

life. But it is no use thinking that since there are going to be future

births, one may as well put off Dhamma practice until then -- for it is

not sure what those future births will be like. And when they come around,

they are just the present moment as well. So no use waiting! Venerable

Nagarjuna shows that it is better to extricate oneself:

"Where birth takes place, quite

naturally

are fear, old age and misery,

disease, desire and death,

As well a mass of other ills.

When birth's no longer brought about

All the links are ever stopped."

-- L.K. 111

Naturally where there is Birth, is also

Old-age and Death.

Twelfth Link:

Old-age and death (jara-marana)

In future one is assured, given enough of

Unknowing and Craving, of lives without end but also of deaths with end.

The one appeals to greed but the other arouses aversion. One without the

other is impossible. But this is the path of heedlessness. The Dhamma-path

leads directly to Deathlessness, the going beyond birth and death, beyond

all dukkha.

The Tibetan picture shows an old man

carrying off a bundled-up corpse upon his back, taking it away to some

charnel ground. My picture has an old man gazing at a coffin enclosing a

corpse. We are well exhorted by the words of Acarya Nagarjuna:

"Do you therefore exert yourself:

At all times try to penetrate

Into the heart of these Four Truths;

For even those who dwell at home,

they will, by understanding them

ford the river of (mental) floods."

-- L.K. 115

This is a very brief outline of the

workings of this wheel which we cling to for our own harm and the hurt of

others. We are the makers of this wheel and the turners of this wheel, but

if we wish it and work for it, we are the ones who can stop this wheel.

The Monster

Both pictures show the Wheel as being in

the grip of a fearful monster. In my drawing the monster's name is

engraved upon his crown so that people should not think of him as a common

demon. He is no such thing, for his name is Impermanence and his crown

shows his authority over all worlds whatever. He devours them and they are

all, heavens and hells together, securely held in the grasp of his taloned

hands. The crown upon his head is adorned with five skulls, representing

the impermanence of the five groups or aggregates comprising the person.

His eyes, ears, nose, and mouth have flames about them, an illustration of

the Exalted One's Third Discourse in which He says: "The eye is afire..."

and so on. Above the monster's two eyes, there is a third one meaning that

while for the fool impermanence is his enemy, for the wise man it helps

him to Enlightenment. Although the monster has adorned himself with

earrings and the like he fails to look attractive -- in the same way, this

world puts on an outer show of beauty puts its beauty fades when examined

more carefully.

Below the painting of the wheel, some

Tibetan examples show parts of a tiger-skin adorning the monster, a symbol

of fearfulness. In my drawing I show the monster's tail which has no

beginning, looping back and forth. In the same way, we have been born,

lived and then died countless times in the whirl of samsara. Sometimes our

deeds were mostly good and sometimes mostly bad, and we have reaped the

fruit of it all.

Some other features

The whole wheel glows with heat and is

surrounded by flames burning with the fires of greed, aversion and

delusion as the Exalted One has repeated many times in His Discourses.

In the upper right corner of both pictures

stands the Exalted Buddha shown crossed over to the Further Shore, meaning

Nibbana. The Tibetan picture shows him pointing out the moon upon which is

drawn a hare, the symbol of renunciation, the way to practice Dhamma, and

the way out of this wheel.[10] In my picture,

He indicates with his hand the nature of samsara and warns us to beware.

He is adorned with a radiance about Him symbolizing the spiritual freedom

and majestic wisdom won by Him which can be described in many ways but is

finally beyond the limitations of everything known to us.

The Tibetan picture shows in the upper

left, a drawing of Avalokitesvara,[11] the

embodiment of compassion as the way and the goal for those who follow the

bodhisattva-path. My picture has the Path of Dhamma of eight lotuses

leading to the wheel of Dhamma. The eight lotuses are the eight factors of

the Noble Path, the first two -- Right View, Right Attitude -- being the

wisdom-section; the next three -- Right Speech, Right Action, Right

Livelihood -- being the morality section; and the last three -- Right

Effort, Right Mindfulness and Right Collectedness -- being the section of

collectedness or meditation. The Wheel of Dhamma has at its center

suññata, the Void, another name for the experience of Nibbana. Around its

hub are the ten petals of a lotus, representing the ten perfecting

qualities (parami) which are necessary for complete attainment:

generosity, moral conduct, renunciation, wisdom, determination, energy,

patience, truthfulness, loving-kindness and equanimity. Eight spokes

radiate from the hub which stand for the practice by the Arahant, the one

perfected, of the Eightfold Path when each factor, instead of being just

right, becomes perfect. On the inside of the wheel's nave there are 37

jewels symbolizing the thirty-seven factors of Enlightenment, while the

outer edge of the nave is adorned with four groups of three jewels showing

the Four Noble Truths in each of the three ways wherein they were viewed

by the Exalted Buddha when he discovered Enlightenment.[12]

Conclusion

[^]

This picture teaches us and reminds us of

many important features of the Dhamma as it was intended to by the

teachers of old. Contemplating all its features frequently helps to give

us true insight into the nature of Samsara. With its help and our own

practice we come to see Dependent Arising in ourselves. When this has been

done thoroughly all the riches of Dhamma will be available to us, not from

books or discussions, nor from listening to others' explanations...

The Exalted Buddha has said:

"Whoever sees Dependent Arising, he sees

Dhamma;

Whoever sees Dhamma, he sees Dependent Arising."

* * *

Anicca vata sankhara

uppada vayadammino

Uppajjitva nirujjhanti

tesam vupasamo sukho.

Conditions truly they are transient

With the nature to arise and cease

Having arisen, then they pass away

Their calming, cessation is happiness.

1. See Wheel No.

34/35: "The Four Noble Truths." [Go back]

2. One of the

eighteen branches of extinct Hinayana. [Go back]

3. the familiar

Pali forms of names are used throughout. [Go back]

4. These have not

been shown in the accompanying drawing and neither does modern Tibetan